Editor’s note: The Slimmer Skimmer is a new feature to give a brief update on a topic critical to marine ecosystem management.

We are starting off our Slimmer Skimmer series with one of fisheries subsidies. The World Trade Organization is currently working to make an end-of-the year deadline (their own, as well as one for the Sustainable Development Goals) to end harmful types of fisheries subsidies. Not all fisheries subsidies are harmful – fisheries management is commonly considered a subsidy, for instance – but the harmful ones encourage overfishing and have substantial negative impacts on marine ecosystems.

Please let us know what you think of this type of feature and if there is anything that you feel we should cover in this format in the future.

Please let us know what you think of this type of feature and if there is anything that you feel we should cover in this format in the future.

So let’s start with a few basics – what are fisheries subsidies?

- Different groups have different definitions of what constitutes a fisheries subsidy. But generally speaking, subsidies are government actions that help the fishing industry increase its income or lower its costs. Examples of fisheries subsidies include fuel subsidies, income supports, price supports, tax credits, tax exemptions, low-interest loans, loan guarantees, regulatory exemptions, and preferential treatment. Many also consider government funding for fisheries management – including monitoring and enforcement efforts – and free access to fishing areas to be subsidies.

- It is estimated that, globally, nations provide ~US$35 billion in subsidies to their fishing industries every year. Some specifics:

- Fuel subsidies and fisheries management are the most common types of subsidies, comprising 22% and 20% of total subsidies respectively. For example, in 2013, China provided ~US$6.5 billion to its fishing industry, almost entirely (94%) as fuel subsidies.

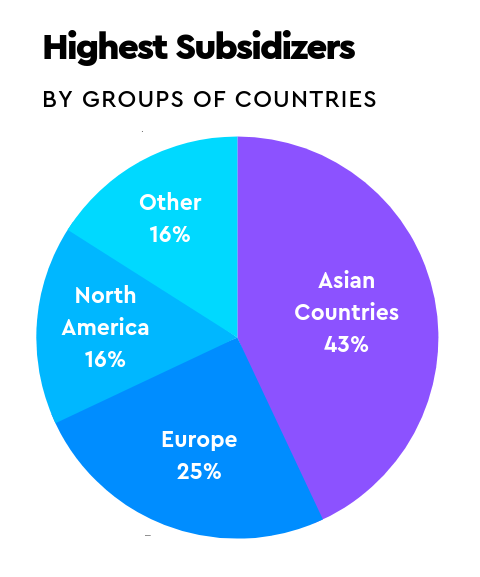

- Regionally, Asian countries provide the most subsidies (beneficial, harmful, and ambiguous) to their fishing industries (43% of the global total) followed by Europe (25% of the global total) and North America (16% of the global total). Japan and China are the highest subsidizing countries (20% each of the global total) with the US coming in a close third.

- Fuel subsidies and fisheries management are the most common types of subsidies, comprising 22% and 20% of total subsidies respectively. For example, in 2013, China provided ~US$6.5 billion to its fishing industry, almost entirely (94%) as fuel subsidies.

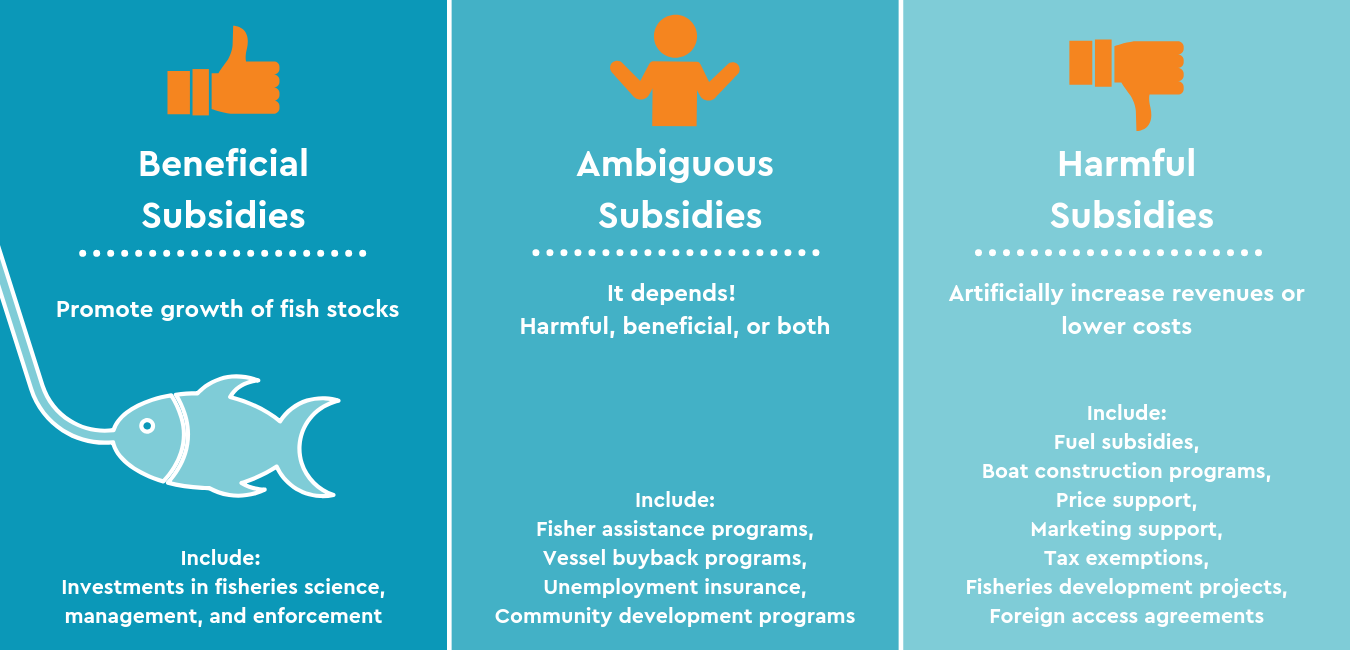

- Fisheries subsidies are considered beneficial, harmful, or ambiguous based on whether they have positive or negative impacts on fisheries resources.

- Beneficial subsidies promote the growth of fish stocks through conservation and the sustainable management of the resource. They include investments in fisheries science, management, and enforcement.

- Harmful subsidies lead to overcapacity and the overexploitation of stocks. In general, harmful subsidies artificially increase revenues or lower costs for fishers. This puts pressure on poorly managed fish stocks and enables fishing entities to continue fishing in situations that would otherwise be unprofitable. This encourages fishers to stay in the industry and keep fishing when they would otherwise leave/stop. Harmful subsidies include fuel subsidies, boat construction programs, price supports, marketing supports, tax exemptions, and payment of fees for foreign access agreements.

- Ambiguous subsidies are programs that could be harmful or beneficial (or both) depending on the details of the program and the local context. They include fisher assistance programs, vessel buyback programs, and community development programs. For example, vessel buyback programs could lead to fewer boats fishing

and reduced fishing capacity as they are generally intended to do. If fishers anticipate that there will be buybacks, however, they may have incentives to overinvest in vessels, leading to an increase in fishing capacity. Another example is unemployment insurance for fishers. An unemployment program could lead to increased safety and reduced effort because fishers do not need to go out in unsafe conditions. If there is a minimum number of fishing days needed to quality for the program, however, the insurance could lead to increased effort and pressure to lengthen the fishing season.

and reduced fishing capacity as they are generally intended to do. If fishers anticipate that there will be buybacks, however, they may have incentives to overinvest in vessels, leading to an increase in fishing capacity. Another example is unemployment insurance for fishers. An unemployment program could lead to increased safety and reduced effort because fishers do not need to go out in unsafe conditions. If there is a minimum number of fishing days needed to quality for the program, however, the insurance could lead to increased effort and pressure to lengthen the fishing season.

- Beneficial subsidies promote the growth of fish stocks through conservation and the sustainable management of the resource. They include investments in fisheries science, management, and enforcement.

- Of the total subsidies provided to fisheries globally, US$20 billion are considered harmful, capacity-enhancing subsidies.

- Of the major subsidizers (the EU, Japan, China, the US, and Russia), the US is the only entity where beneficial subsidies exceed harmful subsidies. (In fact, in the US, harmful and ambiguous subsidies are less than a quarter of the total subsidies to the industry).

Okay, got it. So why do harmful fishery subsidies matter so much for marine ecosystems and some coastal communities?

- Global fishing capacity is estimated to substantially exceed what is needed to bring in the maximum sustainable catch. And the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that 33% of the world’s fish populations are overfished and 60% are being fished to their sustainable limit. Harmful fisheries subsidies that enable excess fishing capacity and effort are considered to be one of the main drivers – if not the main driver – of overfishing. In addition to depleting targeted fish stocks, overfishing also contributes to increased bycatch and damage to marine habitats.

- Harmful subsidies also have substantial negative social impacts.

- Some fisheries subsidies assist fishing fleets engaged in illegal fishing.

- Of the US$35 billion in global annual fisheries subsidies, 65% of the total goes to fishers in developed countries, and 84% of the total goes to large-scale industrial fleets, indicating that large-scale industrial fleets in developed countries are prime – if not the prime – beneficiaries of global fisheries subsidies. Fuel subsidies to large-scale industrial fleets are especially problematic because they allow these fleets to travel vast distances and stay at sea for long periods of time while remaining profitable. These extreme ranges lead to industrial fleets from foreign countries outcompeting domestic, often small-scale fishers in the EEZs of developing countries. Given the importance of small-scale fisheries to food security, nutrition, sustainable livelihoods, and poverty reduction in developing countries, some fisheries subsidies end up hurting some of the world’s most vulnerable communities.

- By encouraging excess fishing effort and overfishing, harmful subsidies actually decrease fishing industry profitability over the medium to long term. For example, a modeling study of North Seas fisheries between 1991 and 2010 found that eliminating subsidies to the industry could increase fisheries profits and the biomass of commercially important species even though total catch and revenue decreased.

- Some fisheries subsidies assist fishing fleets engaged in illegal fishing.

- Some examples of how fisheries subsidies play out in the field:

- It is estimated that high seas fishers get US$4.2 billion a year in subsidies from national governments including those of China, Taiwan, and Russia. Given that the profits from high-seas fishing (without accounting for subsidies) is likely between -US$364 million and +US$1.4 billion, it is likely that there would be substantially less fishing on the high seas if these subsidies were eliminated.

- In 2009, tuna fishers in the Western and Central Pacific got US$335 million in fuel and US$1.2 billion in other subsidies. If you discount profits by the amount of subsidies the industry received, the fleet operated at a loss of more than US$753 million dollars. Furthermore, more than half of the subsidies and 60% of the catch went to fishers from eight developed countries. These subsidies to foreign fishing fleets left local fishers unable to compete for the fisheries resources in their country’s waters.

- Kiribati in the Central Pacific is a prime example of this phenomenon. Over 250,000 tons of tuna – the second largest tuna catch in the world and worth over a billion dollars – are caught annually in Kiribati waters. Virtually none of the tuna is caught by local fishers, and less than 10% of the revenues go to the local economy. Rather, heavily subsidized fishing vessels – such as the Spanish vessel Albatun Tres constructed with an US$8 million subsidy – catch more in a handful of trips than the entire Kiribati fleet can catch in a year. And Kiribati consumers end up paying more for fish because local fishers bring in smaller catches due to competition with foreign vessels.

- Similar scenarios play out in Africa where operating subsidies – such as fuel subsidies – and bilateral fisheries access agreement enable numerous foreign vessels to fish in the EEZs of African nations. These fleets export most of the catch despite the need for these resources to meet Africa’s consumption needs.

- A study of the effects of Vietnam’s fisheries programs found:

- A credit program intended to increase offshore fishing and reduce pressure on inshore fisheries led to an increase in overall fishing effort but did not actually decrease inshore fishing.

- Fuel subsidies led to vessels that would otherwise have been scrapped remaining in operation and increasing the total number of vessels fishing.

- Programs to promote exports led to overcapacity in the processing sector and increased demands on fisheries resources.

- Infrastructure investments proved to be a beneficial subsidy in that it did not substantially encourage entry into the sector and did help increase food safety and hygiene.

- A credit program intended to increase offshore fishing and reduce pressure on inshore fisheries led to an increase in overall fishing effort but did not actually decrease inshore fishing.

- In Malaysia, fuel subsidies benefit larger commercial vessels more than small-scale fishers. What has proven beneficial to smaller vessels owners are monthly stipends.

- Fisheries subsidies are credited with enabling modern-day commercial whaling. In an interesting twist, Japan’s recent resumption of commercial (as opposed to ”research”) whaling in its exclusive economic zone – combined with a decrease in subsidies to the industry – may actually end up curtailing its domestic whaling industry.

- It is estimated that high seas fishers get US$4.2 billion a year in subsidies from national governments including those of China, Taiwan, and Russia. Given that the profits from high-seas fishing (without accounting for subsidies) is likely between -US$364 million and +US$1.4 billion, it is likely that there would be substantially less fishing on the high seas if these subsidies were eliminated.

- Can the negative effects of harmful subsidies be avoided? It is theoretically possible for a highly effective fisheries management system – one capable of setting and actually enforcing sustainable catch limits – to avoid most of the negative effects of harmful subsidies. Even in these systems, however, subsidies increase political pressure to increase effort beyond sustainable levels.

- So, in a nutshell, if there is such a thing as a “no-brainer” in modern marine ecosystem management, eliminating harmful fisheries subsidies is it. As Roberto Azevêdo, director general of the World Trade Organization (WTO), has written, ”In addition to protecting our ocean, an agreement to curb subsidies to fisheries would help ensure the viability of smaller enterprises and create better conditions for economic development in coastal regions.” And as Peter Thomson, the UN secretary general’s special envoy for the ocean put it, “Just think what USD 20 billion could buy in terms of management of marine protected areas, or assistance to artisanal fishers in developing countries!” [Editor’s note: Presumably this assistance to artisanal fishers would come in the form of beneficial subsidies!]

Why are we talking about this right now?

- The World Trade Organization (WTO), a 164-member state organization focused on regulating international trade, has been discussing the need to reform fisheries subsidies since 1999. At its 2017 conference, ministers set a goal to adopt an agreement in 2019 that:

- Prohibits certain forms of fisheries subsidies that ‘contribute to overcapacity and overfishing’

- Eliminate subsidies that contribute to IUU fishing.

- Prohibits certain forms of fisheries subsidies that ‘contribute to overcapacity and overfishing’

At that time, they also formally recognized the need to ensure that least developed countries were part of the negotiations and that developing countries might need ‘special and differential’ treatment.

- Some of the urgency for the WTO to finally reach an agreement after nearly 20 years of discussing the issue is due to the fact that UN Sustainable Development Goal 14.6, adopted in 2015, calls for eliminating fisheries subsidies which contribute to overcapacity and overfishing and IUU fishing by 2020. (Most other SDGs have target completion dates of 2030.)

- Given that the WTO has postponed its next ministerial conference until 2020, the actual elimination of harmful subsidies by 2020 probably isn’t possible unless the WTO holds a special session later this year. But the WTO is actively negotiating an agreement on fisheries subsidies with a near-term deadline.

- If you want to dig more into the nitty-gritty details of the negotiations, you can find a good overview of many of the issues here and a brief update on some of the proposals here. As you can imagine, there are many difficult issues, including the fact that there is currently no globally agreed upon definition of an overfished stock.

Tools for fisheries assessment and monitoring in data and capacity-limited situations

- Some proposals before the WTO would base what kinds and amounts of subsidies are allowed on how healthy and well-managed fish stocks are. Many nations, however, do not have the capacity or resources to do full stock assessments or conduct fleet monitoring/surveillance.

- Tools for assessing and monitoring fisheries in data and capacity-limited situations exist and are increasingly available to help in these situations. The Pew Charitable Trusts provides an overview of many of these tools – e.g., the Data-Limited Methods Toolkit, the Adaptive Fisheries Assessment and Management Toolkit, FishPath, Abalobi, FAME (Futuristic Aviation and Maritime Enterprise), OurFish, and Global Fishing Watch – and other relevant resources.