Editor’s note: Every month, I skim dozens of newsletters, reports, and articles for material relevant to managing and conserving marine ecosystems. And every month, I’m a little shellshocked by the onslaught of bad news. People ask me how I like my job, and I tell them that I love the oceans, I love the work, and I love the people I work with, but it is profoundly sad to chronicle the decline of ocean ecosystems. I know many Skimmer readers have these same – and perhaps even more intense – feelings and experiences. Several recent studies and a body of recent reporting are now providing a framework for recognizing and legitimizing these feelings and experiences as well as highlighting the need to develop systems to deal with them. This Skimmer provides a brief summary of recent research and news in the hopes it can help marine conservation and management practitioners move forward with their vital work studying, managing, and protecting marine ecosystems.

What is ecological grief?

- As professionals in the marine conservation and management field, Skimmer readers are hyperaware of large scale and global changes to marine ecosystems – changes including loss of biodiversity, top predators, iconic species, and biomass and the degradation of habitats. These changes are due to climate change, overfishing, coastal development, and other human activities.

- New research is now examining the emotional and psychological toll that these changes are having on people, especially:

- People who work to protect and understand natural ecosystems

- People whose cultures and livelihoods depend on healthy, functioning natural ecosystems

- People with other close relationships to the natural environment.

A landmark 2018 paper uses the term “ecological grief” to describe the “grief, pain, sadness, or suffering” people feel due to the loss or anticipated loss of beloved ecosystems, landscapes, seascapes, species, and places. These losses can arise from both acute events (e.g., storms or marine heatwaves) and gradual environmental changes (e.g., rising ocean temperatures). And they can be felt as both individual losses as well as collective losses of a group.

- In this 2018 paper, the authors Ashlee Cunsolo and Neville Ellis identify three contexts for ecological grief:

- Grief associated with physical ecological losses such as the disappearance, degradation, and death of ecosystems, landscapes, seascapes, and species

- Grief associated with loss of environmental knowledge and identity such as when people with close relationships to the natural environment feel like they no longer understand the environment, can no longer pass on their environmental knowledge to others, have lost the environment as part of their identity, and/or have lost the environment as a source of pride

- Grief and anxiety associated with anticipated future losses, including loss of culture and livelihoods. [Editor’s note: “Ecological anxiety” or “eco-anxiety” – anxiety about ecological disasters and environmental threats such as climate change and pollution – appears to be a closely-related concept and may be an aspect of ecological grief.]

- Ecological grief can be expressed through “mental and emotional reactions such as sadness, distress, despair, anger, fear, helplessness, hopelessness, depression, pre- and post-traumatic stress.”

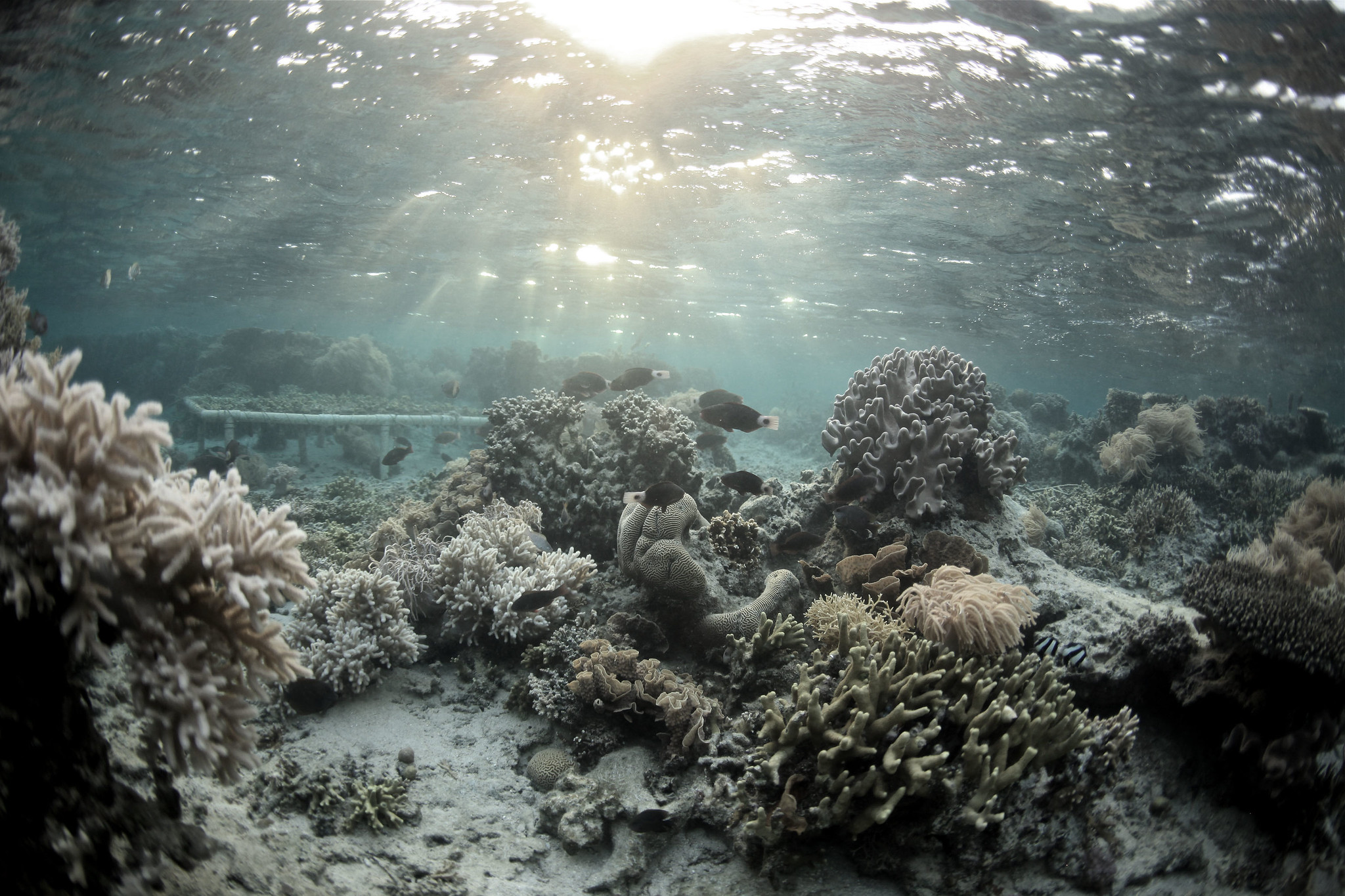

- A 2019 study of “reef grief” looked at some of the impacts of marine ecosystem loss – in this case, coral bleaching and mortality in the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem off the coast of Australia – on mental health and well-being. Researchers led by Nadine Marshall asked local residents, national and international visitors, and people whose livelihoods depend on the reef to rate their level of grief at the ecological losses of the reef on 10-point scale (with 10 being the highest level). Half of local residents, tourists, and tourism operators and a quarter of fishers rated their level of grief at the ecological losses of the reef as an 8, 9, or 10.

- This research builds on a well-established body of research (see references here) showing that natural environments are critical to people’s physical and mental health and well-being, as well as their cultural and community identities – and that degradation, loss, and threats to ecosystems and places threatens mental health and leads to loss of well-being.

- In addition, ecological grief is just one distinct aspect of a wide range of mental health consequences of climate change. Environmental changes and weather events related to climate change (e.g., increased temperatures, increased periods of precipitation, heat waves, droughts, more frequent and more intense hurricanes and wildfires) have been linked to feelings of sadness, distress, despair, anger, fear, helplessness, hopelessness, and stress as well as increased rates of depression, anxiety, pre- and post-traumatic stress disorder, drug and alcohol usage, and suicide. For example, heat waves have been observed to affect neural regulation and weaken people’s ability to regulate emotions.

“Climate change is not just an abstract scientific concept. Rather it is the source of much hitherto unacknowledged emotional and psychological pain, particularly for people who remain deeply connected to, and observant of, the natural world.”

—- Ashlee Cunsolo and Neville Ellis, “Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss” published in Nature Climate Change, 2018

How does ecological grief affect those in conservation and management?

- Research on ecological grief and anxiety is in its very early stages, so there is no definitive picture of who is at the most risk of experiencing ecological grief. Furthermore, emotional responses to similar stimuli vary tremendously between cultures, individuals, and even the same individual at different times in their life. However, initial observations suggest that ecological grief is more common:

- Among people who have close living and working relationships to the natural environment than among people who do not;

- Among people who experience acute weather-related disasters than among people who experience gradual climate change impacts;

- Among people who live in areas with high climate risk and who are most vulnerable to those risks than among people who live in lower risk areas and/or are less vulnerable to those risks.

- In addition, the intensity of ecological grief is likely to be related to the value attributed to the ecological loss. In the 2019 study of “reef grief”, researchers found that those that valued the Great Barrier Reef primarily for its aesthetics (as opposed to valuing it for cultural and social identity, as a source of pride, for a sense of place, as a source of biodiversity, as an economic engine, or as supporting a lifestyle) experience less grief, possibly because they only go to see undamaged areas of the reef.

- Undoubtedly, however, some of the groups hardest hit by ecological grief will be (and are) people who study climate change and its impacts and who work to manage and conserve natural environments and ecosystems. These groups are immersed in the details of global change on a daily basis and have to deal with:

- Data that indicate that ecological and social catastrophes are likely

- Denial of and attacks on their scientific work (and sometimes their own safety)

- Failure of policymakers and society to heed their warnings and take the dramatic actions needed to minimize climate change impacts.

- A recent study and a body of recent news reporting have started to document scientists’ feelings of grief and distress in response to climate change and environmental losses (see here, here, here, and here). In these reports, climate scientists use the terms “acute mental health crisis”, “emotionally exhausted”, “broken hearted, “profound sadness and loss”, and “tired of processing this incredible and immense decline” to describe their feelings and emotional states. They also describe feelings of deep grief and anxiety, rage at political inaction, and inadequacy because they are not doing enough to ward off climate change impacts. And they describe thinking obsessively about climate change impacts, becoming disconnected and isolated from others, and having trouble sleeping and enjoying life. (On the flip side, some also described feelings of hope and motivation and were impressed and encouraged by the idealism, hopefulness, and lack of despair among younger people and their colleagues. Scientists also expressed feelings of relief and hope now that the general public is finally becoming aware of the full implications of climate change and showing concern).

- In one of the few formal studies of how global change is impacting scientists, Lesly Head and Theresa Harada’s 2017 paper looked at the emotional management strategies of a sample of Australian atmospheric climate scientists and environmental scientists. They found that scientists used a range of behaviors to manage their emotions around climate change and the future and to persist in their work. These behaviors included:

- Suppressing painful emotions such as anxiety, fear, and loss and developing “compulsory optimism”

- Avoiding thoughts or discussion of work when not working, including avoiding discussing climate change in social situations

- Avoiding discussion of climate change with their children because of worries about leaving them distressed and disempowered

- Using dark or “graveyard”/”gallows” humor

- Embracing “normal” routines and the quotidian (e.g., reading novels, drinking tea) to maintain a sense of self

- Becoming stoic and “thick skinned” to “laugh off” attacks (including accusations of fraud, hate mail, and even death threats) from climate denialists.

- A particularly critical theme in this study (as well as in other interviews with climate scientists and conservation/management professionals, e.g., here and here) is the perceived need to separate emotions from the practice and communication of science. Western scientific culture emphasizes rationality and views emotion as inferior and antithetical to reason. This creates strong social and cultural pressure on climate scientists to be dispassionate, restrained, and “positive” in their research and communication. This pressure is problematic for several reasons.

- This false binary between reason and emotion in Western science interferes with an aggressive response to the mental health challenges of those who are dealing with ecological grief. Scientists who speak out and deal openly with the emotional aspects of their work may have valid concerns about suffering professional consequences such as diminished standing in the academic community and being less competitive for receiving grants and promotions.

- It can lead to a bias towards the “reverse of alarmism” in which scientists demand much greater levels of evidence for “surprising, dramatic, or alarming conclusions” than they do for other results.

- This false binary between reason and emotion in Western science interferes with an aggressive response to the mental health challenges of those who are dealing with ecological grief. Scientists who speak out and deal openly with the emotional aspects of their work may have valid concerns about suffering professional consequences such as diminished standing in the academic community and being less competitive for receiving grants and promotions.

“We’re documenting the destruction of the world’s most beautiful and valuable ecosystems, and it’s impossible to remain emotionally detached… When you spend your life studying places like the Great Barrier Reef or the Arctic ice caps, and then watch them bleach into rubble fields or melt into the sea, it hits you really hard. The emotional burden of this kind of research should not be underestimated.”

—- Tim Gordon and Andy Radford, quoted in “Scientists ‘must be allowed to cry’ about destruction of nature” published in Science Daily in October 2019

Why is ecological grief unique?

- There are a number of reasons why ecological grief is different than other forms of grief. For starters, ecological losses are only beginning to be recognized and legitimized as a source of grief. Recent research has referred to ecological grief as “disenfranchised grief” because it is often overlooked or not publicly acknowledged and as such is not addressed in discussions of climate change or climate change policy or research. Terminology such as ecological grief is still brand new, and suffering from ecological grief still feels “irrational and inappropriate” to some.

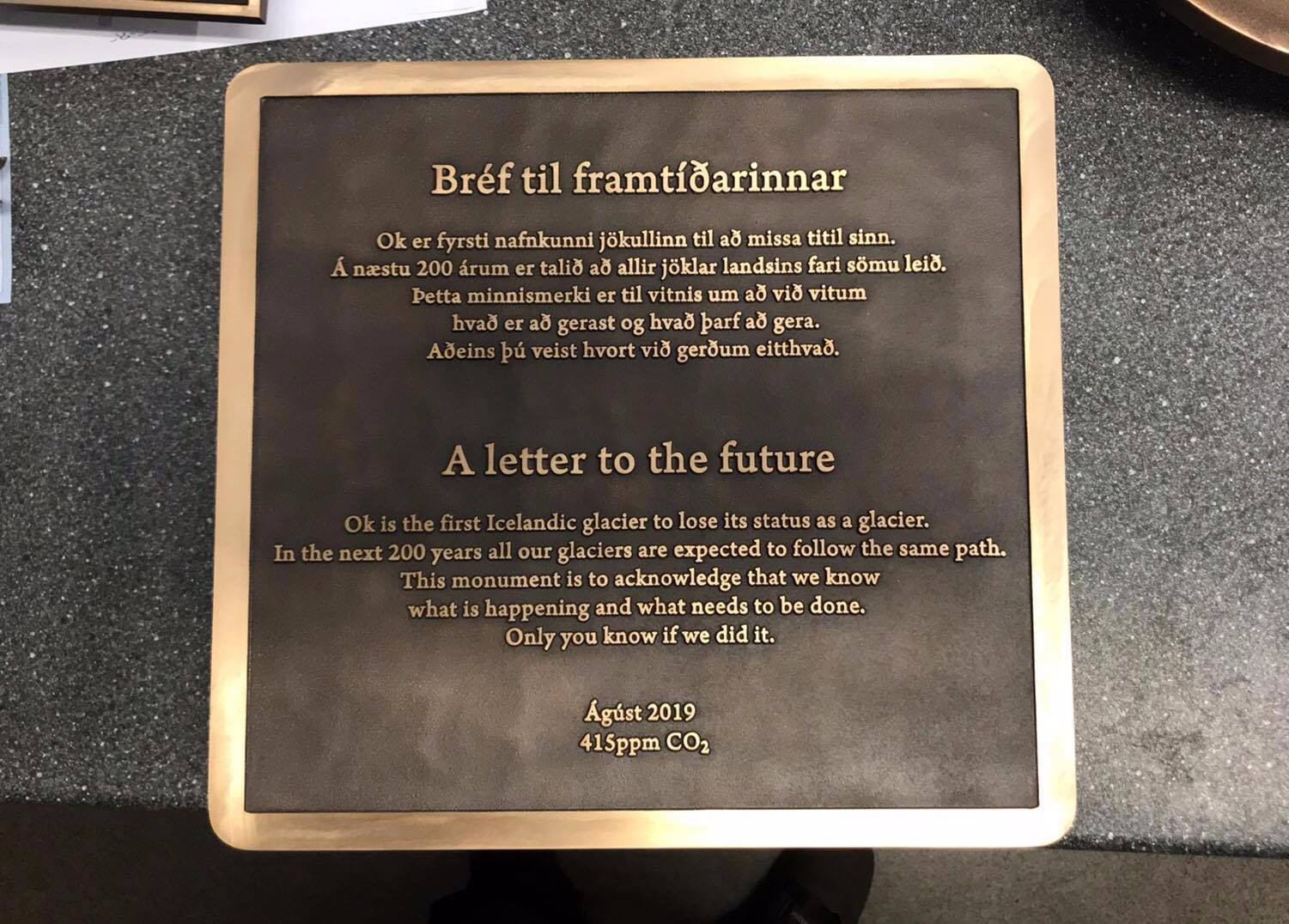

- Second, while humans have been causing broadscale change to natural environments for a long time, the current scope and pace of change is unprecedented, and society has not yet fully developed rituals and practices (such as funerals) to help people express their emotions, receive the support of community, and heal from ecological losses in the same way that it has for human losses. Examples of rituals and practices to help people manage ecological grief and sustain associations with places and practices that have been lost are starting to emerge, however. Examples include:

- A funeral and plaque in Iceland to commemorate the 700-year old Ok Glacier, Iceland’s first major glacier loss

- A ceremony in Switzerland to commemorate the “dying” Pizol Glacier.

Other possibilities for memorials include museums, artwork, films, music, and stories.

- Third, ecological grief is often due to future losses or things that will never come to fruition. For example, people are mourning cultural activities in which that future generations will never get to participate in and species that future generations will never get to see. Many young adults are actually deciding not to have children because of fears of future societal and environmental conditions and concerns about the environmental impacts of adding to the global population. While society recognizes the grief associated with losing a child, it does not have a process for mourning children who are wanted but never born.

- Finally, many losses are “slow” losses that are continuing and even accelerating over time, making it “grief without end” that is particularly difficult to heal from.

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is to live alone in a world of wounds.”

—– Aldo Leopold, Sand County Almanac, 1949

Where do we go from here?

- Ecological grief and the need for mental health programs and services related to it are likely to become more common as impacts from climate change become more prevalent. Addressing these needs effectively requires actions on numerous fronts – including academic research, development of therapeutic practice, and institutional and policy changes.

- In terms of research and development of practice, the authors of the Consolo and Ellis 2018 study of ecological grief as a result of climate-change related loss highlighted the following needs for developing the science and treatment of ecological grief:

- Greater conceptual and theoretical development of the concept of ecological grief

- Increased understanding of vulnerability to and risk factors for ecological grief, including the interplay with personality, culture, and environment

- Increased understanding of the relative impact of different types of losses, e.g., landscapes, ecosystems

- Increased understanding of how ecological grief relates to similar concepts such as eco-anxiety

- Development of interventions and therapies to reduce suffering and promote coping.

Some particularly important questions revolve around the degree to which our understandings and treatments of other forms of grief can be used to help address ecological grief. In particular, can models for dealing with traditional grief – for working through it and rebuilding lives – be adapted to deal with ecological grief? Or do ongoing ecological losses mean sufferers are more likely to get stuck in a grieving process?

- Some of these questions/areas are being addressed as part of a new “science of loss” associated with environmental change. This developing area stresses the need to plan and prepare for loss to minimize its consequences. Doing this involves:

- Developing understanding of what people value about the natural environment and how climate change will impact it

- From this knowledge, developing strategies for minimizing and managing grief.

As an example, research shows that when communities have to be resettled, harms can be minimized by allowing enough time for planning, compensating people for their economic losses, taking measures to maintain community cohesion and social networks, and providing resources to the resettled and host communities.

- A 2016 seminal paper on the science of loss by Barnett and colleagues suggests that working with communities where loss is likely to occur can help them take ownership of it and make the likely losses into something “less existentially troubling.” They also discuss harnessing loss to “capture its productive possibilities and minimize its destructive consequences.” Both in this work and in the article on “reef grief”, authors see a silver lining in ecological grief in be that it can strengthen and inspire people to better protect beloved places such as the Great Barrier Reef and prevent further losses.

- For those involved in environmental conservation and management as well as climate-related science, institutions can play a critical role in helping their employees deal with ecological grief. Institutions – academic, governmental, and other – employing people who work to understand and protect natural ecosystems need to:

- Fully recognize grief as a natural and legitimate response to ecological change

- Provide programming and supports for employees dealing from ecological grief, similar to how other professions – disaster relief, law enforcement, military, and health care – have strategies and structures for helping employees manage emotional distress. Programming and supports could include trainings, debriefings, support groups, and counseling.

Building effective systems to help employees dealing with ecological grief can facilitate “healthy” grieving and psychological recovery and reduce the risk of long-term mental health impacts. This in turn can lead to better decision making and work performance and make people more resilient to future trauma.

- An example of what such a program can look like is the US-based Adaptive Mind Project launched in 2017. This program works to help coastal professionals build their psychological and social coping capacities and shift organizational cultures so that they can continue their work protecting coastal ecosystems and communities. Other examples of organizations and groups that support people dealing with ecological grief in their work and personal lives include the Climate Psychiatry Alliance, Refugia Retreats, the Eco-Grief Support Circle, and the Good Grief Network.

- At a policy level, ecological grief needs to be accounted for when analyzing the impacts and costs of climate change so that these impacts and costs to society are not undervalued.

- And, finally, how can marine conservation and management practitioners deal with their ecological grief at a personal level? In interviews, climate scientists and conservation and management practitioners (here, here, and here) describe a variety of self-care practices including:

- Exercising, meditating, seeking therapy, eating and drinking more healthily, creating art, drinking more wine, and spending time with family and friends

- Tuning out the news and avoiding thinking about the future and/or things outside their control.

In addition, they are also doing what they can at an individual level. In a recent article about climate-related “eco-anxiety” among young people, mental health care professionals stressed the need for those of all ages to find the “empowered middle ground” between paralysis in the face of catastrophe and ignoring the problem. They recommend focusing on taking individual actions to work towards a solution and recognizing that progress can be made. Climate scientists and conservation and management practitioners (here, here, and here) are particularly capable of this at an individual level because of their professional expertise, and they describe taking individual action by:

- Advocating for change by tweeting, campaigning, and giving talks and teaching

- Reducing their own personal carbon footprint by commuting by bike or public transportation, telecommuting, buying offsets for flights, putting up solar panels, becoming a vegetarian, and driving a hybrid vehicle

- Working harder to publish their work more quickly

- Celebrating small wins.

How are you dealing with ecological grief? Share your stories about dealing with ecological grief with other Skimmer readers by writing to skimmer@secure308.inmotionhosting.com/~octogr5.

Figure 1: Dying coral reef. Picture from https://www.flickr.com/photos/worldworldworld/6975915640

Figure 2: A plaque placed at the former location of the Icelandic Okjökull glacier, which disappeared due to climate change. Picture from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Okj%C3%B6kull_glacier_commemorative_plaque.jpg

Figure 3: DTSJ bike commuter #Cycling. Picture from https://www.flickr.com/photos/bike/18660594993