Editor’s note: Anthropogenic noise in the ocean – from ships, sonar, construction, oil wells, windfarms, seismic surveys, and other activities – harms marine animals ranging from marine mammals to fish to invertebrates. Ocean noise has been documented to:

- Increase egg and larval mortality, cause developmental delays, slow growth rates, and increase bodily malformations

- Cause temporary or permanent hearing loss

- Increase stress, change metabolic rates and oxygen consumption, decrease immune responses, reduce energy reserves, and decrease reproductive rates

- Cause alarm responses, decrease predator avoidance responses, compromise reproductive and offspring rearing activities, and interfere with feeding

- Inhibit intraspecies communication and more.

As the Skimmer is covering various way that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted marine ecosystems and communities, a likely reduction in ocean noise is one possible bright spot. As we collected news and research articles on this topic, however, almost all reports that we found related to ocean noise and marine mammals off the West Coasts of the U.S. and Canada in the first half of 2020. To help broaden our understanding, we asked scientists from Applied Ocean Sciences, a collective of ocean consultants with expertise in ocean acoustics, to share what they have learned about noise trajectories over a longer timescale and in other areas of the world. Below is our Skimmer-style summary of news and research articles and an interview with Chris Verlinden, a senior scientist and chief technology officer at Applied Ocean Solutions.

Part 1: “An unprecedented pause in ocean noise that probably hasn’t been experienced in decades”: A summary of ocean noise news from the COVID-19 pandemic

- Decreases in shipping, cruise ship traffic, ferry traffic, whale watching tours, and recreational boating led to a significant decrease in the low-frequency noise associated with ships during the first half of 2020. Pandemic safety concerns and economic slowdowns also decreased a multitude of other activities that generate ocean noise including fishing, aquaculture, seismic exploration, oil drilling, military exercises, offshore construction, and dredging activity for at least some portion of the pandemic.

- While relatively few specific measurements have been published to date, one early assessment of the first quarter of 2020 found that reduced ship traffic between Asia and the ports of Vancouver and Seattle (on the order of a 20% reduction from the same period of 2019) lowered noise power levels in the deep water offshore of Vancouver Island by about a quarter and in the Strait of Georgia by nearly half. Ferry service in the region was cut after this period, so ocean noise levels at the height of the pandemic were likely even lower than the levels measured in this study.

- Another report found that median daily sound levels in Glacier Bay, Alaska, decreased by half relative to the year before due to fewer cruise ships and whale watching tours.

- In reports from other areas of the world, major ports in the northeast U.S. saw a nearly 50% decrease in ship traffic in April 2020 compared to April 2019, while ship traffic for large European ports – including Antwerp, Belgium; Le Havre, France; Lisbon, Portugal; and Rotterdam, Netherlands – dropped by a quarter that month.

- Decreases in vessel traffic during the early pandemic were not universal, however, with recreational boating increasing in some areas such as Sarasota, Florida, in the U.S.

- These slowdowns have created an extraordinary opportunity for researchers to examine how marine mammals sensitive to low frequency ocean noise change their behavior when noise levels drop.

- Biologists in Glacier Bay, Alaska, have observed behavioral changes such as humpback whales napping, socializing, and feeding in the middle of shipping channels.

- Orcas off the coast of Scotland and Canada have been observed closer to shore than usual.

- One hypothesized change is more frequent and complex communication between individuals since ocean noise is associated with a decrease in calling behavior for whales in the region.

- The COVID-19 pandemic is reminiscent of another catastrophe – the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 – when a halt in world trade and travel led to dramatic reductions in ocean noise. Researchers studying North Atlantic right whales in the Bay of Fundy, Canada, found that their hormone levels related to stress decreased when vessel traffic and consequently ocean noise decreased.

- Researchers in Monterey Bay, California, are conducting similar research in that they sampled the stress hormones of humpback whales in the bay in April and May 2020 and will compare them to samples collected when vessel traffic returns to normal. One critical difference, however, is that all boat and air traffic stopped in the days after the September 11 attacks, while offshore shipping has continued during the pandemic even as small boat and tanker traffic in the bay declined.

- The news is not all good for marine mammals, however, as pandemic-related shutdowns have interfered with annual health assessments of marine mammal populations and other marine mammal research as well as loss of funding for marine mammal conservation initiatives.

- Data on changes to ocean noise are slow to emerge during the pandemic because most hydrophones are not set up to telemeter their measurements and the pandemic has led to delays in servicing hydrophones (and recovering their data) by ship. An ongoing discovery of hydrophones that can be used for a global analysis of the effects of the pandemic on ocean sound has found the most hydrophones in U.S., Canadian, and European waters as well as the Weddell Sea with relatively few in other parts of the world.

Part 2: “In many parts of the ocean a whale might be audible twice as far away in 2020 as in 2019”: Interview with Chris Verlinden of Applied Ocean Sciences

Skimmer: We know the pandemic led to some dramatic decreases in ocean noise in the first half of 2020, but many noise-producing ocean uses have picked back up (e.g., shipping, fishing) since then. What can you tell us about changes in the ocean soundscape from before the pandemic to now – one year in?

Verlinden: Great question. The financial shutdown associated with the COVID-19 pandemic led to a dramatic decrease in certain types of shipping activity all over the world. It is important to note that this decrease was not uniform geographically or across vessel types. Cruise ship traffic all but disappeared during the height of the pandemic and has not yet returned to its pre-pandemic numbers. Similar reductions occurred in some passenger ferry routes where the number of vessels required to fill the needs of the community decreased during the height of the pandemic. Ferry routes, at least in the U.S., have now largely returned to pre-pandemic levels. Recreational fishing traffic (charters, sport fishing, deep sea fishing, etc.) decreased dramatically in the U.S. early in the pandemic, while most commercial fishing traffic continued at its pre-pandemic levels. Traffic from military vessels remained fairly constant, as did survey and research vessel traffic. Tanker traffic experienced a drop from the second half of March into April of last year but then steadily rose to pre-pandemic rates by the end of the year. Container vessel traffic experienced a similar trend in March and April 2020 but is only now starting to increase. Interestingly, bulk carrier traffic along certain areas on the U.S. West Coast decreased dramatically in March and April 2020, more than container traffic. This traffic included cargo such as gravel, chemicals, and bulk agricultural goods such as wheat and lumber. This made certain areas, such as the mouth of the Colombia River, substantially less trafficked and thus quieter than usual.

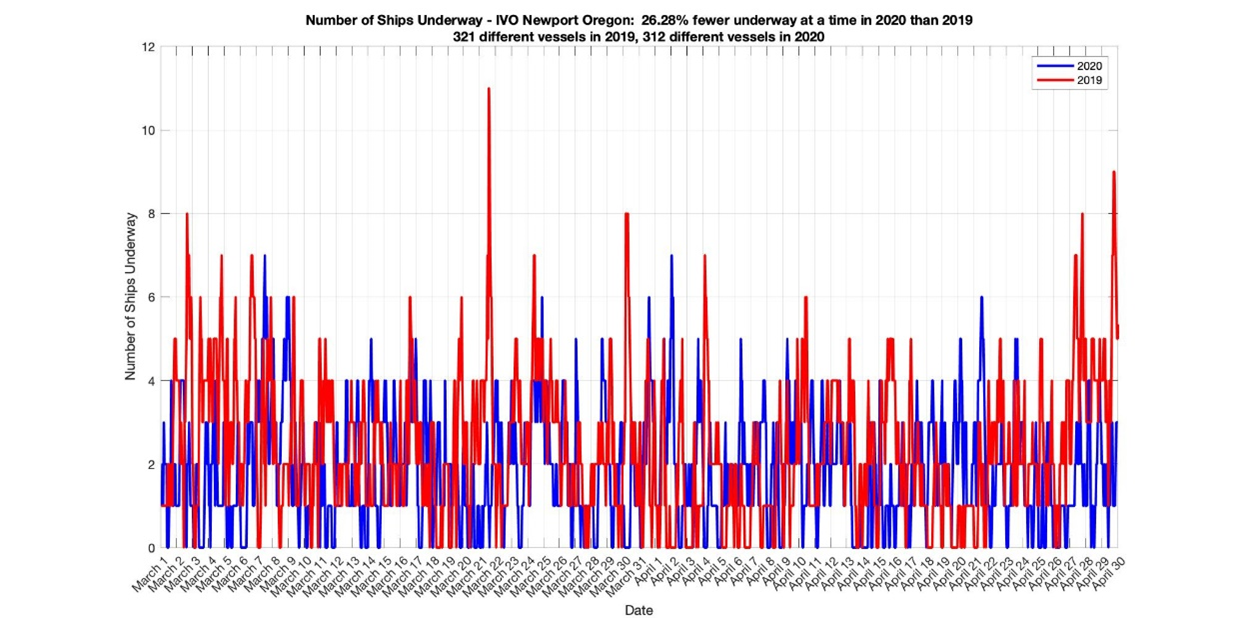

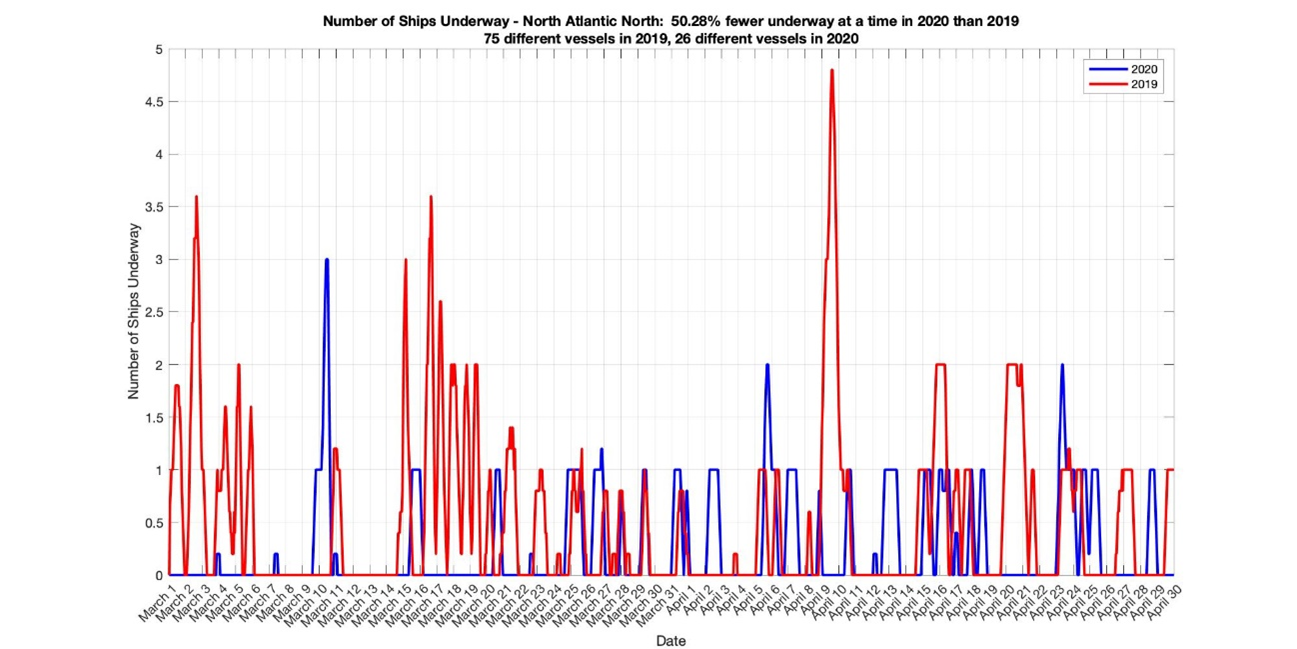

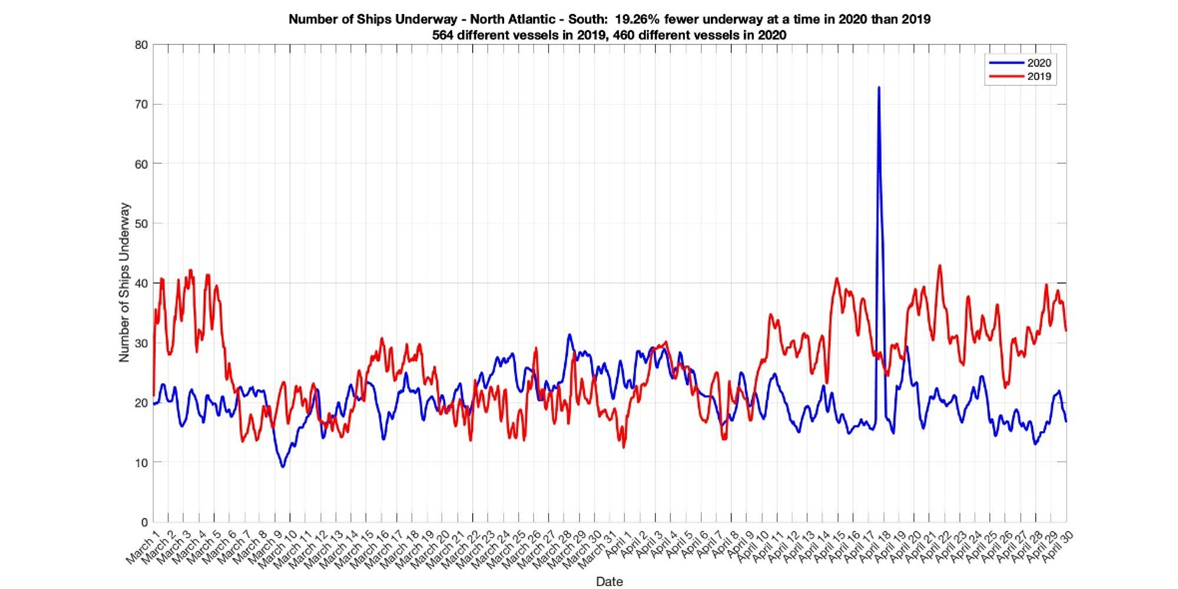

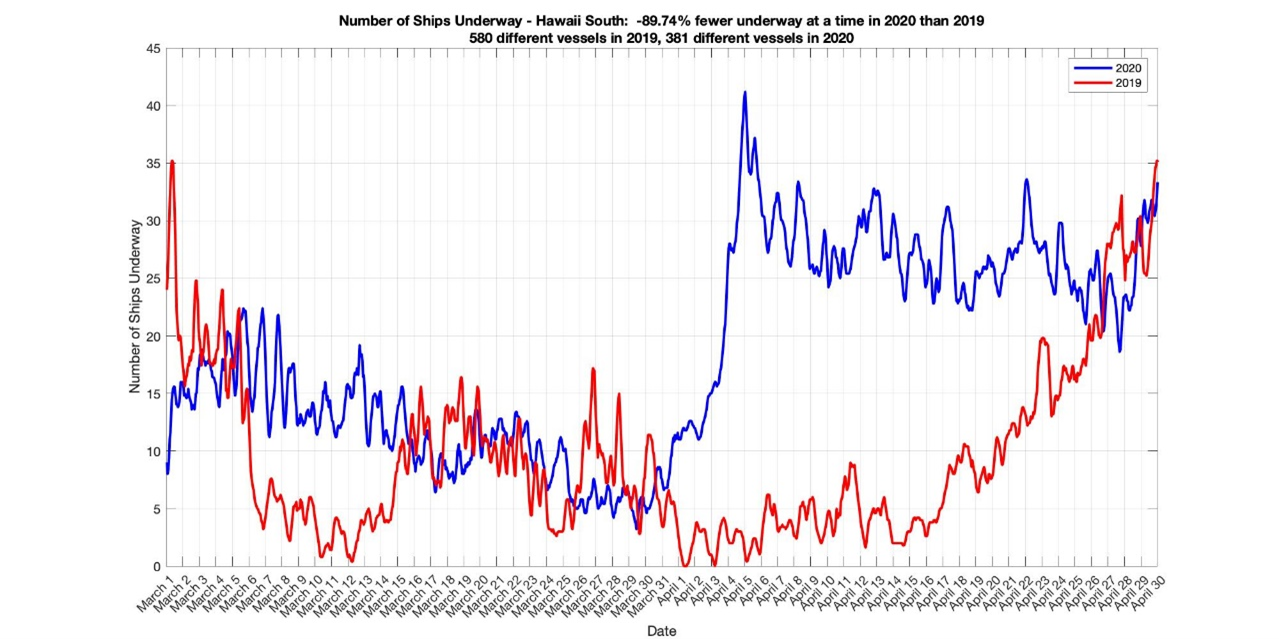

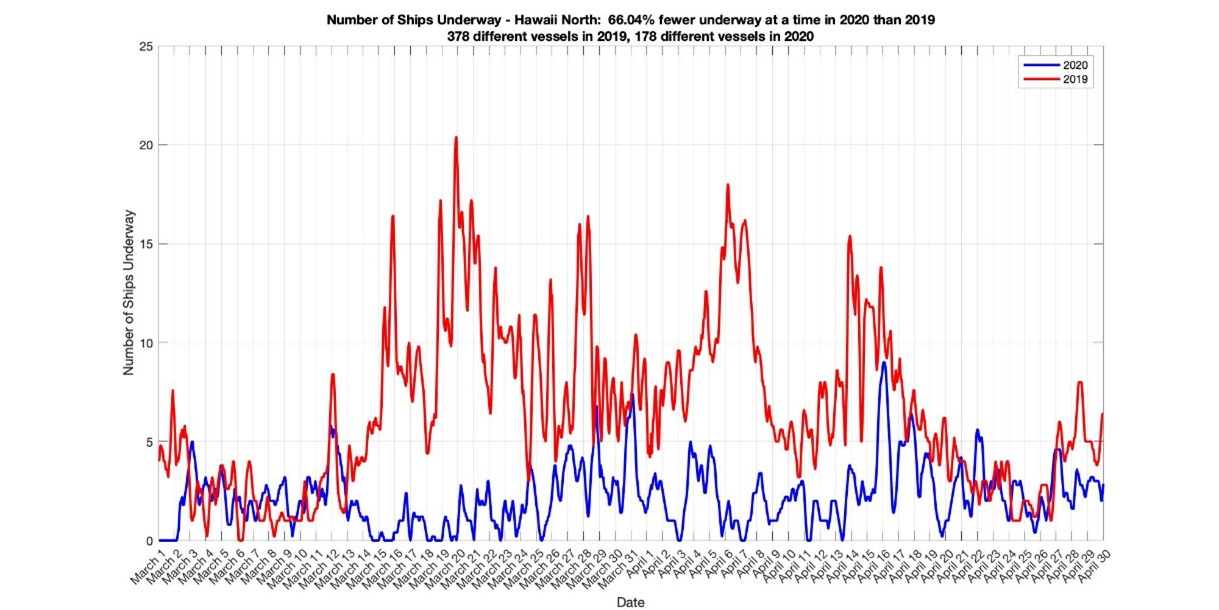

These trends by vessel type were roughly similar across the U.S. So in areas where much of the vessel traffic was cruise ships (such as parts of south central or southeast Alaska), ocean noise decreased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Below are several plots of the number of vessels underway in a few different areas of U.S. waters during March-April 2019 and 2020. You can see that it varies dramatically with regard to geography. Most of this traffic is expected to return to usual pre-pandemic levels, with the possible exception of the cruise ship industry.

So in a nutshell, changes to shipping traffic depends on the type of traffic and location. But for the most part, shipping levels dropped dramatically in most places in the U.S. in the latter half of March 2020 into April and have increased to nearly pre-pandemic levels in most places for most types of vessels.

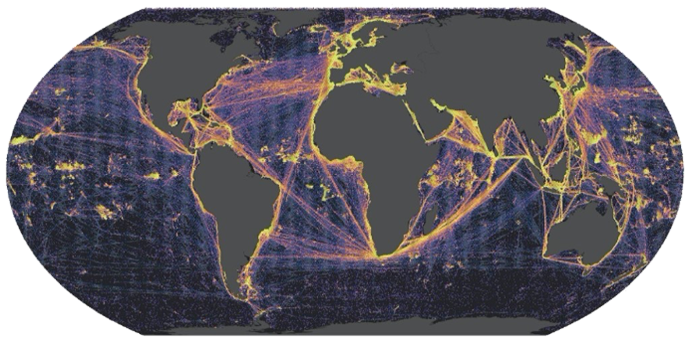

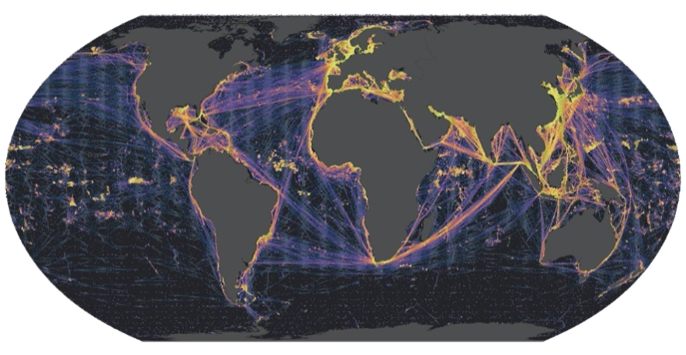

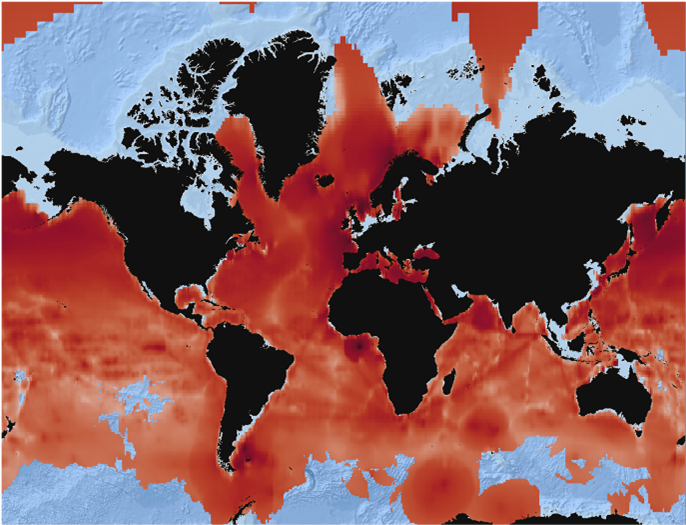

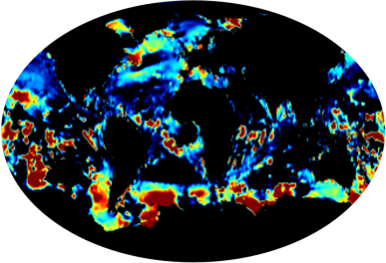

Now let’s talk about the acoustic implications. It is important to note that the acoustic impact of a ship depends on a lot of variables such as the vessel type and speed as well as local oceanographic characteristics, bathymetry, and ocean bottom properties. Sound propagates differently in deep water versus shallow water and in cold water versus more temperate waters. For these reasons, the changes in ambient ocean noise from ship traffic do not mirror the changes in shipping density. Also, there are other sources of noise in the ocean including wind, waves, industrial activity, seismic disturbances, ice, and biologics such as whales, fish, and shrimp. All these things taken together are referred to as the soundscape. So, the changes in the global soundscape are a more nuanced discussion than the changes in shipping activity. Below are some figures that illustrate this. The figures on top show global ship densities (from Spire Inc. global AIS data) in 2019 (top) and 2020 (bottom). You can see a subtle reduction in density in the major lanes in 2020.

Now let’s look at figures with the average modeled global shipping noise from 2019 (top), 2020 (middle), and the difference (bottom).

Our models predict that most of the ocean was quieter in April 2020 than April 2019, an average of about 3 dB quieter. That might not sound like a lot, but decibels are logarithmic so 3 dB represents a doubling of intensity. This means that in many parts of the ocean a whale might be audible twice as far away in 2020 as in 2019. That’s a big deal.

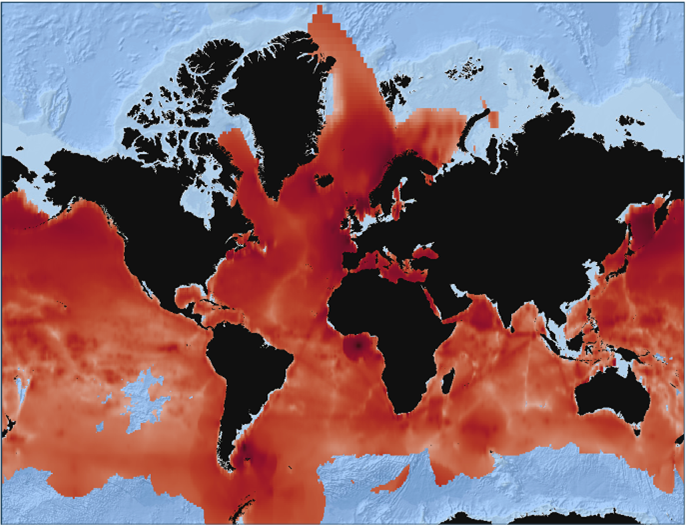

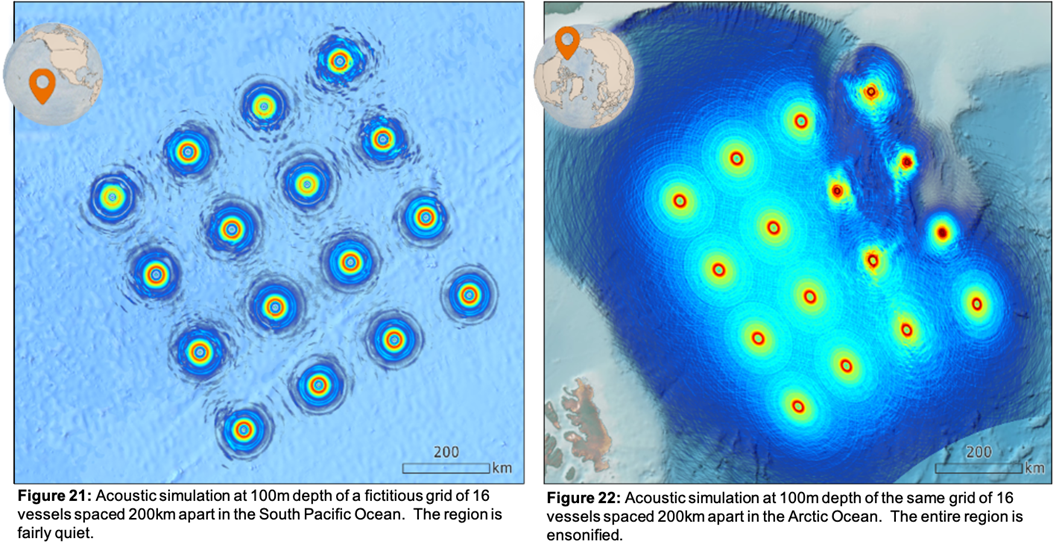

Also, not all areas are impacted the same. Below are plots of what a fictional grid of 16 ships will sound like at the surface of the ocean in the South Pacific compared to the Arctic. The cold water at the surface in the Arctic traps sound near the surface because of a phenomenon known as surface ducting. So if you reduce the number of ships in the Arctic by a couple of ships, the average noise level near the surface will decrease dramatically, while reducing the number of ships in the tropics will not have as big of an impact.

So, long story short: many areas of the global ocean were quieter in 2020 than 2019 due to the reduction in shipping associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The average difference was about 3dB, which is significant for marine mammals and other organisms. In most locations, the difference was most pronounced in April 2020. Since that time, vessel traffic and thus the soundscape have been returning to pre-pandemic levels. The acoustic impact is not uniform and does not follow trends in shipping perfectly due to oceanographic and environmental factors. I expect ship noise to return to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2021 and then continue the trend of increasing. Most literature reports that the ocean gets louder by an average of 3 dB per decade, although some recent research suggests the current trend may be closer to 1-2 dB per decade. I expect this rate of increase to continue for the foreseeable future with our increasingly globalized economy driving more shipping, and by extension, more shipping noise.

That being said, this rate of increase will likely not occur uniformly, and I am most concerned about noise levels in the Arctic. With the cold surface temperatures, surface ducting, and organisms evolved for a very quiet region, the continued increase in vessel activity in the Arctic will make it a lot louder over the next couple decades and have a significant negative impact on the native marine mammal populations.

Skimmer: What upcoming data are you most interested in seeing to help us better understand how changes in ocean uses during the pandemic are altering ocean soundscapes and ecosystems?

Verlinden: Model and observational data comparison. The Arctic. Marine mammal stress hormones.

The pandemic gave us a rare opportunity to study the impact of reducing ship traffic on the global soundscape. It is rare that we, as scientists, can see precisely how these knobs are being adjusted. Let’s not waste it. Let’s see what happened during 2020 and how it impacted the marine organisms that rely on sound to survive. Applied Ocean Sciences’ approach has been to model the global ship noise, but that is only part of the story. We need to compare these models to actual observations and adjust our model parameters until we can reproduce the observed data. We can then use those models to estimate and infer the soundscape everywhere. If our models can reproduce the changes that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, it will improve our confidence in our ability to model the soundscape everywhere in the world under a variety of circumstances. This includes forecasting the soundscape under projected future shipping and industrial activity levels. I’d particularly like to apply this knowledge to the Arctic to predict soundscape changes over the next 10-50 years.

Finally, I’d love to see what the marine mammal stress physiology community comes out with over the next few years. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, marine biologists recorded a reduction in stress hormones such as cortisol and aldosterone in marine mammals in the Bay of Fundy. This directly correlated with the reduction in ship traffic that followed those attacks. I am interested and excited to see if this is observed on a global scale during the COVID-19 pandemic and see what we can learn about the impact of ship noise on marine mammal population health using these observations. The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting changes in shipping and ship noise has provided us with an amazing opportunity to understand how ship noise impacts marine mammals so that we can better address the challenges faced by these animals in the future.