Editor’s note: In our last issue, The Skimmer heard from coastal and marine tourism operators and experts from around the world (including Indonesia, Brazil, the Mediterranean, and the US) about the diverse ways that the COVID-19 pandemic is currently affecting coastal and marine tourism, how it is likely to change coastal and marine tourism in the future, and what impacts this is likely to have on coastal and marine ecosystems. We received comments from additional experts about how the pandemic is affecting other communities such as the surfing community and British Columbia, Canada, and aspects of coastal/marine tourism such as beach management.

Lindsay Usher: Surfing in the time of coronavirus

Editor’s note: Lindsay Usher is associate professor of park, recreation, and tourism studies at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, US.

The surfing community has been on a rollercoaster since the COVID-19 pandemic came to the United States. On March 19, California issued a stay-at-home order, and some surf communities, such as San Diego, closed their beaches to everyone. Other localities, such as Ventura County, closed their parking lots but still allowed exercise on the beach and in the water. As governors across the country began issuing stay-at-home orders, there was considerable confusion at some beaches about whether surfing was allowed. For instance:

- The City of Virginia Beach (in the state of Virginia) had to clarify its rules the day after issuing them to state that surfing was allowed because it was considered exercise.

- The Surfrider Foundation, an environmental organization based in the US that was started by surfers, rolled out the #stayhomeshredlater hashtag campaign to encourage surfers to honor the stay-at-home orders

- Surfline, a popular surf forecasting website, started the #shredathome hashtag campaign and featured movies and other digital content for surfers stuck in their homes. The site also featured an article from the chief lifeguard in San Diego arguing that surfers should not paddle out during the pandemic because they might strain first responder resources if they got into trouble.

As organizations like Surfrider and Surfline tried to follow the science to develop their stances on surfing, the scientific community was beginning to study the virus and ways it could be transmitted. Once scientific findings became available (e.g., the virus likely could not be transmitted through spray from a breaking wave; it was not as likely to be transmitted via touching surfaces; etc.) and governments began loosening restrictions, the surf world modified its guidance. Surfrider changed its hashtag campaign to #shredsafely, and Surfline began providing more detailed forecasts.

Amid all this were regular surfers who had to navigate new local, state, and federal guidelines and advice from their own organizations and websites. I began a study (ongoing) in mid-April to understand surfers’ experiences of the pandemic and the ensuing regulations around the world. We have learned that some surfers were confused about whether they should be going surfing, even if it was allowed. If they were supposed to stay at home, did that mean they could only surf if they could walk or bike to the beach? Some would try to get to the beach before lifeguards or law enforcement began to patrol (8 or 9am). One participant went at night because there was a bioluminescence event occurring during a full moon in California. Others felt guilty for surfing if their beach was open because they knew many beaches were closed. Surfers’ interactions with others changed: they did not hang around the parking lot to talk to friends after surfing. Many surfers had their surf travel plans disrupted.

The regulations frustrated some because surfing is a naturally socially distant activity – surfers dislike crowds and try to avoid being within 6 feet of one another when there is not a pandemic. For surfers who were not allowed to surf, they did other activities to stay sane and in shape: prone paddling, skateboarding, biking, and yoga are a few examples. For many who were able to go surfing, it was a way to relieve stress and cope with the stay-at-home orders that altered everyone’s way of life. As more states have opened up, surfers are still taking precautions, but they seem more confident that surfing is one of the safest activities they can engage in right now.

Ulsía Urrea Mariño: Reopening beaches during the COVID-19 pandemic

Editor’s note: Ulsía Urrea Mariño is a doctoral student at the Harte Research Institute of Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi and a lecturer in the sustainable management of coastal zones at National Autonomous University of Mexico. She is also a member of the Ibero-American Beach Management and Certification Network (PROPLAYAS) and Altamare SC where she participated in creation of recommendations and guidelines for reopening Mexican beaches.

The COVID-19 pandemic is indeed an event unprecedented in the last 100 years, and social life on the planet has been disrupted. Beaches – spaces in which economic and recreational activities related to tourism take place – are no exception. Tourism is the economic activity most affected by mandatory lockdowns, travel restrictions, and the business closures to avoid the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

It is also true that this new reality allows us to look at the practices that seem ‘common’ and discuss them. In the case of beach management, this new scenario has been called ‘the New Normality in Beaches,’ and it seeks to rescue the good practices of conventional beach management, innovate in the measures that the pandemic imposes, and rethink how we interact on and with the beach.

Of the good practices of conventional beach management, several elements are rescued:

- Full identification of beach operators at the local level

- Solid waste management

- Cleaning schemes (continuous and emerging)

- Surveillance schemes

- Signage to provide relevant information to visitors

- Environmental education campaigns

- Maintenance of water quality for human activities

- Certification schemes

- Construction and maintenance of beach accesses

- Construction and maintenance of necessary infrastructure such as lifeguard towers, bathrooms, parking lots, and information kiosks, among others.

Nevertheless, the first question to be addressed is how these elements common to beach management need to be modified in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some examples include:

- Full identification of beach operators at the local level: If we take Mexico as an example, beaches are administered and managed by municipalities. However, not all beaches in a municipality have management schemes. Usually, the management is for urban or tourist beaches. Thus, of the 11,500+ linear kilometers of beaches in Mexico, just under 100 have a certification such as Blue Flag or White Flag (granted by the Mexican government).

- Solid waste management: Before the pandemic, solid waste management did not include biologically infectious waste such as masks or gloves. In this new scenario, one must have a mask to access any public space, and the beach is no exception. The challenge is to make sure this waste is disposed of correctly, including environmental education campaigns to raise awareness.

- Cleaning schemes (continuous and emerging): Although there are more questions than answers regarding the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in seawater and sand, taking measures to sanitize the sand with chemical products such as bleach is an undesirable practice on beaches. On the other hand, cleaning beach furniture, kiosks, and bathrooms more regularly is wise.

- Surveillance schemes: In addition to surveillance tasks to ensure the safety of beach visitors, during the pandemic it is necessary to monitor beach access and social distancing to ensure compliance with necessary sanitary measures. Periodic drone flight systems and the refinement of user counting systems have been implemented for these purposes.

- The use of signage to provide relevant information about the beach in particular to visitors: As a result of the pandemic, signage has changed to include messages about ‘the correct use of the mask,’ ‘walkable spaces and rest spaces on the beach,’ ‘social distancing,’ and ‘number of visitors to the beach in real-time’ to name a few.

- Construction and maintenance of access to beaches: More and more beach operators, at various levels of government, have developed mobile and web applications that allow beach users to reserve their spaces (as in South Korea) or provide real-time information about the capacity of beaches (Portugal, South Korea, and Argentina). In South Korea, the mobile application generates a QR code that allows beachgoers to be contacted if there is a COVID-19 outbreak associated with the beach they visited.

As we have seen, conventional beach management measures have remained, but have changed to meet the needs imposed by the pandemic. Will these emerging measures be sustained over time, even when the pandemic is over? Will these emerging measures become permanent? Of course, each beach is a different reality, and some will incorporate – while others will not – the emerging measures in their permanent beach management schemes.

Ronnie Noonan: Tracking the use of ocean spaces during the pandemic

Editor’s notes: Ronnie Noonan is the marine science communications director at eOceans. eOceans is a collaborative scientific initiative based in Canada that works to inform ocean conservation with crowd-sourced information.

We launched our global project “Our Ocean in COVID-19” project – which involves a new mobile app and analytics platform – early in the pandemic to support ocean researchers and explorers in tracking the ocean during the pandemic. The project is led by 28 researchers in 14 countries (and counting), including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Iceland, Indonesia, Netherlands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Mozambique, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Thailand, and Timor-Leste. We are collaborating with local marine tourism operators and ocean organizations to spread the word about the project and increase awareness and participation. Through this project, we are studying how policies that control human movement and use of the ocean – ranging from full prohibitions on people leaving their homes to restricted ocean access points and tourism to no closures or restrictions at all – change over time and impact social, anthropogenic, and ecological patterns at local and global scales.

Our goal is to help communities track how ocean usage, wildlife encounters, and anthropogenic impacts (such as pollution) change over the course of the pandemic and on into the new normal. We hypothesize that the response of coastal and marine tourism will depend on each area’s restrictions on human confinement. In Atlantic Canada, there was a large influx of beach goers in March (which is very cold!) when businesses initially shut down. Of course, that shifted again when confinement policies became stricter and beaches closed. Now that both beaches and businesses have re-opened in Atlantic Canada, we will be looking to see how ocean usage, wildlife observations, and anthropogenic impacts change. [On a personal note, I have never had more beach days in a summer!]

These behavior changes may not only highlight how important coastlines and oceans are to people at this time but may also provide early insights into how tourism and ocean use patterns will change in the coming years. For instance, the demand for tourism may start to correspond to fluctuations in pandemic restrictions and less on seasonality, and coastal and marine tourism may cease completely in some areas that do not have alternative economic sources or in areas that cannot rely on local customers.

While the lack of tourism is hard on developed countries, it is devastating to many developing countries. Tourism is the main economic driver for many small, coastal communities. Without the influx of funds from tourism, residents are returning to unsustainable and destructive fishing practices for subsistence, and many communities are seeing outsiders come to fish in their waters illegally, including in marine protected areas. Marine tourism operators are concerned for the well-being of their ecosystems and fear that areas may become too degraded to attract tourists in the future. These communities also rely heavily on tourism to fund conservation efforts. Without this funding, protected areas cannot be enforced, and decades of effort are at risk of being lost.

Our project is also tracking wildlife interactions during this time. Where human confinement is strictest and enforced, we expect wildlife observations to increase. If you would like to get involved, please visit www.eoceans.co/project-covid19 to learn more. Every observation is useful, even if it is just an empty beach!

June Pretzer: The view from British Columbia, Canada

Editor’s note: June Pretzer works in ecological restoration on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in environmental management and sustainability at Royal Roads University with a focus on restoration of coastal ecosystem services.

If you looked across the Strait of Juan de Fuca a year ago, freighters would be plying their way to Vancouver ports, cruise ships would be tying up at Ogden Point in Victoria, and international pleasure craft ranging from small sailboats to super-yachts would be a common site. Today, not so much.

The Canadian provincial and Federal response to COVID-19 was swift, implementing measures to protect communities from infection while laying out plans for gradual reopening. British Columbia declared a State of Emergency, mandated physical distancing, encouraged hand washing and wearing face masks, and prohibited gatherings of more than 50 people. The Federal government banned entry by foreign nationals, closed the Canada-US border, and mandated self-isolation for all returning travelers. Transport Minister Marc Garneau issued an order banning cruise ships from operating in Canadian waters until October 31, 2020. BC Ferries reduced service by half, and Canadians were encouraged to socialize within a bubble of family and selected others to ‘flatten the curve’. These measures prevented rapid spread of the virus so that in British Columbia we are now in Stage Three of a four-stage approach to re-opening.

Health guidelines and measures such as Transport Canada’s COVID-19 guidelines that specified the maximum number of persons allowed per vessel had an immediate impact on marine tourism, effectively shutting down all marine operations, parks, and accommodations. While some marine operators such as Prince of Whales Whale Watching in Victoria continued to operate with greatly reduced passenger numbers, increased sanitization between trips, and higher overall costs, some marine operators that offered overnight sail tours shut down operation for the summer. The complete lack of cruise ships was definitely a game changer for the Victoria Harbour Authority that had over 260 ship visits and over 1 million cruise ship passengers and crew visits in 2019 – double the population of Vancouver Island. For many people working in the marine tourism industry, this is not a summer to get rich.

However, there are good things. British Columbians who might head off to distant places are instead heading to local seas, woods, and wineries for a taste of summer. They are turning to personal watercraft such as paddle boards and kayaks to bring them closer to nature. Paddle-powered vessels impact marine wildlife less than motorized vessels and they are accessible to a wide level of abilities. Tour operators are adjusting to COVID guidelines through new and innovative operations. PacificSUP Victoria’s (Stand up Paddle Boards) mobile business plan provides contactless board delivery and sanitized gear to beach or lake locations with rentals, lessons, and tours. Such a mobile business model uses no land-based resources and has a smaller environmental footprint. Phil Foster of West Coast Outdoor Adventure sees day tours usurping overnight trips and is training students to meet the higher demand. Moving to Stage Three of the British Columbia Restart Program means eateries can reopen with social distancing guidelines and no-touch QR Code-generated menus. People are rethinking what our new normal can be and looking for opportunities to adapt. We have even learned how to keep a safe distance at the beach.

There are also expected benefits to marine wildlife and coastal seascapes. Reduction in marine traffic has reduced discharge from ships as well as marine noise levels. Reduction in vessels such as cruise ships reduces exposure of all marine life to an estimated 32 billion liters of potentially dangerous sewage, greywater, and washwater discharged annually in British Columbia coastal waters. Based on hydrophonic records, Oceanwise reports a reduction in marine noise levels throughout British Columbia marine waters. Marine noise from shipping interferes with marine mammal communication, and a reduction in both of these factors means a respite for marine life ranging from southern resident orcas to filter feeders.

As we move into Stage Three, parks and businesses are re-opening. With social distancing, regular hand hygiene, and a general acceptance of when and where to mask up, British Columbians are adapting to our new normal. This is not to say that challenges will not continue for the marine tourism industry. However, the general consensus is that COVID-19 is here to stay for a while at least, so if we want to survive, we had best practice some adaptive management and look for innovative ways to move forward. With our beautiful coastline to explore and the general need to ‘get outside’, tourism will change and adapt and may be better for doing so.

The author thanks the following people for sharing their observations and experiences: Phil Foster of West Coast Adventures, Ian McPhee of Prince of Whales Whale Watching, Oceanwise, Jacklyn Barr of WWF, and Rhonda Ready.

Briana Bombana: Three scenarios for beach management in the pandemic and recovery

Editor’s note: Briana Bombana is an oceanographer and researcher with the SGR INTERFASE Research Group at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a consultant with Santosantos Tourism Care. She is also a member of the Ibero-American Beach Management and Certification Network (PROPLAYAS) and one of the editors/authors of the PROPLAYAS recommendations for sun and beach tourism in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the present year, the Sars-COV-2 virus has been a different sort of ‘visitor’ that has led authorities to impose mobility and social restrictions on most of the human population to curb its contagion. In the case of mass tourism, the consequences of these restrictions are widely distributed between harms and benefits – for example, the loss of jobs that have negatively impacted tourism infrastructure and services and the simultaneous recovery of some cultural and natural assets. While these outcomes are not yet fully evaluated, we can say that the pandemic has already defied the certainty of a continuous flow of people and resources around the globe, the base of mass tourism.

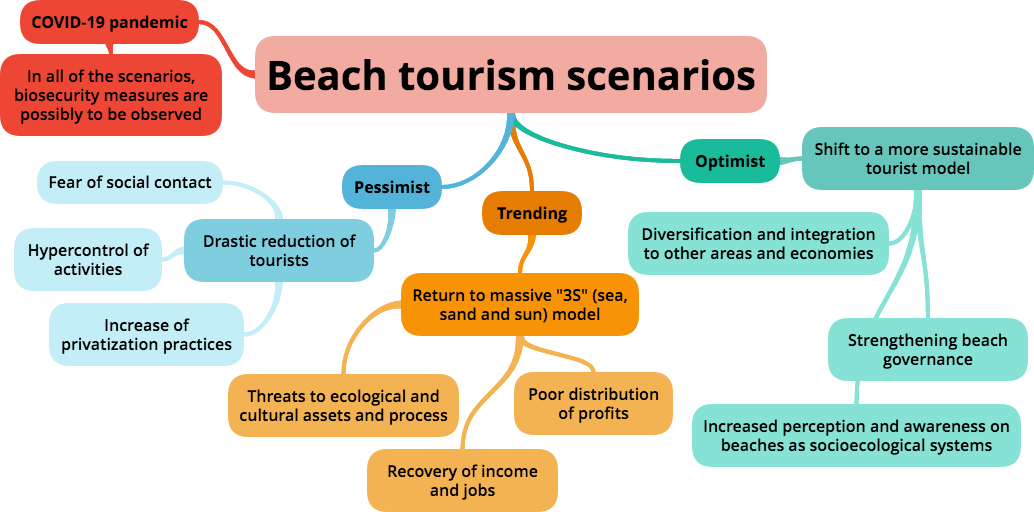

To tackle the current urgency and help design management actions for tourist beaches, the Ibero-American Beach Management and Certification Network (PROPLAYAS) approximated three possible scenarios and general recommendations for the pandemic and recovery, following a potential vaccine. These scenarios are:

- Pessimistic scenario: Epidemiologic risks remain as does fear of social contact, perpetuating biosecurity measures and beach use restrictions, potentially leading to privatization practices, exclusion of informal workers and small businesses, unemployment, and other conflicts.

- Trending scenario: Gradually the ‘normality’ from before the pandemic returns. Initially there is a boom of beach users from the local area; then national tourism returns, followed by international tourism. In this scenario, with the exception of biosecurity measures, management actions common to mass tourism centralized on recreational activities remain the same. Income and profits recover, pressuring natural and cultural assets.

- Optimistic scenario: A new paradigm for beach tourism emerges after learning from this crisis. It aims for resilience by promoting cultural and ecological conservation practices on beaches that are integrated with the management of the surrounding area. In addition, public access and health care are pursued.

Regarding the recommendations, an evaluation of their usefulness is advised for each case. Most of them target the optimistic scenario, such as a shift to a ‘slow’ tourism focused on nearby places and in which cooperation between informal workers and small businesses could be endured.

Figure credits:

Figure 1: Photo courtesy of Lindsay Usher.

Figure 2: From the "Liable coastal county” infographic series by Altamare SC, previously published on social media. Figure courtesy of Ulsía Urrea Mariño.

Figure 3: Figure courtesy of eOceans.

Figure 4: Photo by June Pretzer, MSc Candidate, Royal Roads University.

Figure 5: Adapted from the Proplayas report and subsequent discussions within this Network. Figure courtesy of Briana Bombana.