The Skimmer is a new MEAM feature where we review the latest news and research on a particular topic. News about the Arctic Ocean region[1] is coming fast and furious these days, and it can be difficult to see how all the individual pieces fit together. In this Skimmer, MEAM pulls together news and research related to Arctic marine ecosystems from the past year. Our takeaway: The situation is grim for the Arctic as we knew it, and this has global repercussions.

The Skimmer is a new MEAM feature where we review the latest news and research on a particular topic. News about the Arctic Ocean region[1] is coming fast and furious these days, and it can be difficult to see how all the individual pieces fit together. In this Skimmer, MEAM pulls together news and research related to Arctic marine ecosystems from the past year. Our takeaway: The situation is grim for the Arctic as we knew it, and this has global repercussions.

How is the Arctic climate changing? Let us count the ways

- The Arctic has been in the news a LOT even in the past few weeks as air temperatures in February climbed above freezing at the North Pole making it 30° C warmer than normal.

- At the same time, Europe went into a deep freeze. Why? Climatologists think these weather anomalies are related and are due to a weakening of the “polar vortex”, a low pressure system around the North Pole that keeps cold air trapped in that region. Climate change may be weakening this vortex, making these weather events more common.

- Aside from recent weather patterns, what’s been going on with the Arctic climate overall? In a nutshell, huge changes. The Arctic is warming at least twice as fast as the rest of the planet. In NOAA’s latest Arctic Report Card released in December 2017 (covering the year October 2016 to September 2017), scientists found:

- The average surface air temperature in the high Arctic last year was the second warmest since 1900. Only 2016 was warmer.

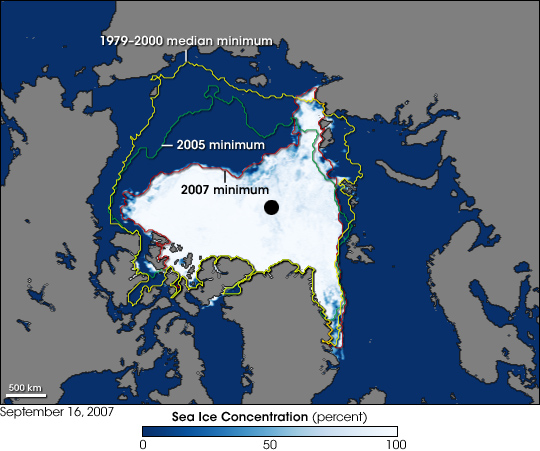

- There was a lot less sea ice last winter than there used to be. The winter maximum sea ice recorded in March 2017 was the lowest on record since 1979.

The decrease in summer sea ice was even more dramatic. The minimum sea ice extent in September 2017 was 25% lower than the 1981-2010 average sea ice extent and was the second lowest on record (tied with 2007).

The decrease in summer sea ice was even more dramatic. The minimum sea ice extent in September 2017 was 25% lower than the 1981-2010 average sea ice extent and was the second lowest on record (tied with 2007).

- The ice in the central Arctic is young and thin. Only 21% of the sea ice cover in 2017 was older than a year. In 1985, older, thicker ice was 45% of sea ice cover. Other recent studies suggest that the total volume of Arctic sea ice in late summer is about one-fifth of what it was in 1980. Why does this matter? Young, thin ice melts away faster than older, thicker ice.

- Sea surface temperatures in the Barents and Chukchi seas were much warmer than average. In August 2017, they were 4°C warmer than average, contributing to a delay in autumn freezing.

- Primary production has increased in the Barents and Eurasian Arctic seas because sea ice is breaking up earlier in the year, allowing sunlight to reach the upper layers of the ocean and stimulate plankton blooms.

- The Greenland ice sheet has been melting at an average of ~265 Gt/year over the past 15 years. This melting is the largest single contributor to global sea level rise and is a relatively new phenomenon. Prior to the 1980s, there was relatively little summer melting of the ice sheet. It now experiences melting over most of its surface in some years. 2017 wasn’t as bad as normal, however, and had below-average melt due to a cooler spring and summer.

- And while it is not the focus of this Skimmer, we would mention that on land, the Arctic tundra is greening and the permafrost is melting. Plants are getting larger, and trees and shrubs are taking over grasslands. Snow cover was actually up in Asia this past year, though, and it had the highest spring snow extent since 1967. But snow cover was low in the North American Arctic, with communities such as Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow), Alaska, experiencing earlier snow melt.

- In general, these changes create dramatic feedback loops and affect regional and global climate because:

- Dark surfaces absorb more heat (the albedo effect), and the change from white ice and snow to blue water and green land is increasing regional and global temperatures. One study estimates that that the albedo effect is equivalent to 25% of the global temperature increase from rising CO2 levels over the past 30 years. So, yes, this is a big deal.

- Warmer air holds more moisture, so the now-warmer Arctic air holds more water vapor than it used to. Water vapor is a greenhouse gas, leading to further temperature increases.

Meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet runs down holes in the ice sheet called moulins. This lubricates the ice sheet bed below and causes outlet glaciers at the edge of the ice sheet to advance more quickly and calve more icebergs into the ocean.

Meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet runs down holes in the ice sheet called moulins. This lubricates the ice sheet bed below and causes outlet glaciers at the edge of the ice sheet to advance more quickly and calve more icebergs into the ocean.

- As terrestrial regions in the Arctic get warmer, runoff from snowmelt and other streams flow through warmer land, leading to warmer water flowing into the Arctic Ocean from northward-flowing rivers in Siberia and Canada.

- As permafrost thaws, ancient bacteria frozen for thousands of year, are coming back to life and converting newly thawed plant and animal matter to carbon dioxide and the even more potent greenhouse gas methane. (Not to mention that one of the newly activated bacteria is anthrax which infected a remote herding community in Siberia in 2016, killing a twelve year old boy, and that the methane gas being released by organic decay is highly flammable and is causing explosions in some areas.)

- As more of the Arctic Ocean is ice free in the summer, there is increased wave action which in turn breaks up large ice floes and causes them to melt faster. And larger expanses of open water feed larger storms, which transports heat from warmer surface waters deeper into the water column and inhibits ice formation.

- Similarly, in the eastern Arctic Ocean, as more ice melts due to warmer air temperatures, more vertical mixing is occurring between cold fresh water at the surface of the ocean and warmer salty water below. This decrease in stratification, or “Atlantification”, of Arctic waters warms surface waters and causes more ice to melt.

- Why does all this matter so much to the rest of the world? Because one of the features of current global climates is the circulation of air and ocean currents between the cold Arctic and warmer parts of the Northern Hemisphere. This circulation is driven by the temperature difference between the areas. With a warming Arctic and a smaller temperature gradient, this circulation is diminished. Mid-latitude winds (“jet streams”) weaken and form wavier patterns, slowing down the passage of weather systems. This leads to extreme weather stagnating over places for long periods such that warm weather becomes prolonged heat waves, dry weather becomes droughts (creating conditions ripe for wildfires), and rainfall events cause flooding. (Read more about all this here, here, and here.

- As an example, a new study describes the link between loss of Arctic sea ice and reduced rainfall in California.

- If you need a bit of a mental break after reading about all of this deeply unsettling information, it’s interesting to think about some of the rather unorthodox and VERY unproven measures that some geoengineers are proposing to deal with what’s going on in the Arctic – proposals include putting glaciers on crutches to prevent their sliding into the ocean, thickening sea ice with wind-powered pumps, and spreading reflective material on polar ice to reduce melting rates.

What does all this mean for marine conservation and management?

- As Arctic sea ice continues to hit record lows during both the summer and winter, areas of the Arctic Ocean are becoming accessible to ships (or year-long transit) for the first time in 1,500 years. This means the potential for an influx of fishers, shippers, tourists, explorers, scientists, prospectors, drillers, navies, etc. into the area. Conservation and management just got a lot more complicated…

But, brace yourselves, a bunch of competing nations actually did something conservation-minded

As a bit of background, you should know that as of late 2017 there weren’t any regulations on fishing in the central Arctic Ocean. This is because there isn’t currently any significant fishing in the central Arctic Ocean. But with the recent decreases in sea ice extent and the northward migration of many fishing stocks, the possibility of commercial fishing – particularly for pelagic species like polar cod – exists.

As a bit of background, you should know that as of late 2017 there weren’t any regulations on fishing in the central Arctic Ocean. This is because there isn’t currently any significant fishing in the central Arctic Ocean. But with the recent decreases in sea ice extent and the northward migration of many fishing stocks, the possibility of commercial fishing – particularly for pelagic species like polar cod – exists.

- In a shocking (given the current state of geopolitical affairs) act of proactive and precautionary management, five nations with Arctic borders – Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Russia, and the US – and other nations with industrialized fishing fleets – China, the European Union, Iceland, Japan, and South Korea – have agreed to sign a legally binding treaty to prevent commercial fishing in the central Arctic Ocean for at least the next 16 years.

- This treaty will cover a 2.8 million square kilometer area (an area slightly larger than the Mediterranean Sea), in the middle of the Arctic Ocean outside the Exclusive Economic Zones of the surrounding nations. This area is “high seas” beyond any nation’s jurisdiction and subject to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the UN Fish Stock Agreement, meaning any country could potentially fish there.

- After the initial 16-year term, the treaty will be automatically extended every five years unless a country objects or a science-based fisheries management plan is put in place.

- The agreement will establish a joint scientific research and monitoring program to improve understanding of the area and determine what fish stocks could be harvested on a sustainable basis. This is a good step because we know virtually nothing about harvestable fish in the central Arctic Ocean. Approximately 250 fish species are known to exist in Arctic waters, but very little is known about population sizes, life cycles, habitats, interactions, etc. What we do know, however, is that organisms that live in cold waters are generally slower growing and longer lived and reproduce relatively infrequently. All of these factors make determining sustainable fishing yields pretty hard. So while sixteen years seems like a relatively long time now, it will not seem that way to fisheries scientists who will be starting from scratch in terms of baseline knowledge.

- This international agreement is a good example of “Arctic exceptionalism,” the historic willingness of Russia and the United States to set aside other geopolitical differences for their common interests in the far north. A new blog describes what’s next for this agreement, including formal ratification.

So what’s going on with Arctic marine ecosystems? How are they changing?

- The Arctic Council’s biodiversity working group reported this past year that the Arctic environment is on the verge of a major shift because of:

- Loss of sea ice habitat

- Shifts in species ranges both within the Arctic and from sub-Arctic regions into the Arctic, and

- Increases in contagious diseases such as avian cholera.

- In thinking about all these various factors, the importance of the loss of sea ice to Arctic ecosystems really can’t be overstated. The loss of sea ice is having a massive influence on the climate, oceanography, primary productivity, and all other trophic levels in the Arctic.

- For instance, scientists are just now coming to understand how the loss of sea ice is making the shallow continental shelves around the Arctic Ocean windier and wavier. This in turn is increasing sediment flow from the shelves into the Arctic Ocean. (Sediment discharge into the ocean is approximately twice what it was a decade ago.) These sediments are bringing nutrients, trace metals, and carbon with them and could lead to big changes in the Arctic marine food web.

Furthermore, as sea ice declines, the trophic structures that depends on it are changing. The algae that grow around and under sea ice feed zooplankton that in turn feed fish that in turn feed seals that in turn feed polar bears. A new study demonstrates this link between sea ice algae and polar bear diets and suggests that declines in sea ice (and sea ice algae) may make it impossible for top predators to get the calories they need to survive.

Furthermore, as sea ice declines, the trophic structures that depends on it are changing. The algae that grow around and under sea ice feed zooplankton that in turn feed fish that in turn feed seals that in turn feed polar bears. A new study demonstrates this link between sea ice algae and polar bear diets and suggests that declines in sea ice (and sea ice algae) may make it impossible for top predators to get the calories they need to survive.

- The loss of sea ice is a double whammy for upper trophic level species like seabirds and marine mammals, which use it for all sorts of activities such as feeding, resting, mating, and raising babies. For instance, harp seals in the Barents Sea are getting thinner because they have to travel farther to the ice edge to feed. The early sea ice retreat is reducing breeding and pup rearing habitat for ringed seals. And ivory gull populations are on the decline as their sea ice feeding areas disappear. (Read more about these and other changes here.)

- All of these changes mean that a lot of animals are eating things they did not eat before (e.g., polar bears are now eating ground-nesting common eiders and cliff-nesting murres) and possibly not eating enough. Basically, Arctic food webs are getting all topsy turvy.

- Some species may be benefitting from these changes, but it’s fairly obvious that it’s not polar bears, or at least not all polar bear populations. A recent study found that polar bears have much higher metabolic rates than previously assumed, and the decreased availability of easy pickings (e.g., fatty seals hanging around on or near sea ice) mean that many are running a calorie deficit and using up their fat stores, endangering their survival and the long-term viability of some populations.

- These changes are also suboptimal for indigenous communities in the Arctic, which depend on a lot of marine species for food and vital aspects of their culture.

- In addition, invasive species are rapidly becoming a significant threat to Arctic ecosystems and communities due a warming climate and increasing human activity. New-to-the-Arctic marine species can arrive all sorts of ways including ballast water discharge, hull biofouling, marine debris, docks brought into the region, and the release or escape of live animals. (For example, Russian scientists and managers released the omnivorous red king crab Paralithodes camtschaticus, a monster of a crab – up to 10 kgs and 1.5 m across, into the Barents Sea in the 1960s to establish a fishery.)

- All of this creates a tremendous need to improve biodiversity monitoring in the Arctic to provide information to policy makers more quickly. The Arctic Council has lots of ideas on how to do this.

- It’s not all doom and gloom in the Arctic. Increased exploration of Arctic ecosystems is leading to some fascinating discoveries, like diatoms that live on the underside of sea ice that can photosynthesize with incredibly small amounts of light. These diatoms have the lowest light level threshold ever recorded for active photosynthesis and are a critical source of nutrients in Arctic ecosystems, particularly during seasons when algal plankton are not abundant.

Now let’s talk some more about boats in the Arctic

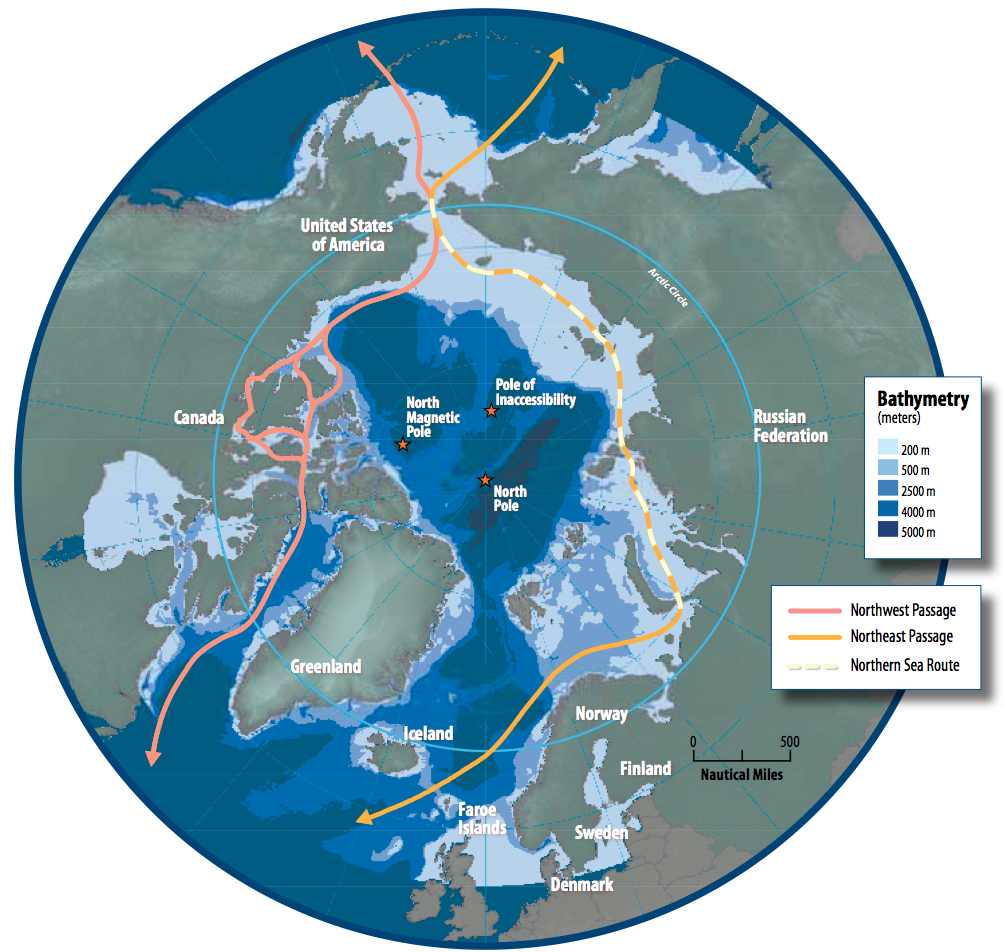

This past summer (Summer 2017), a Russian commercial vessel, a tanker carrying liquid natural gas, transited the Arctic’s Northeast Passage without an icebreaker for the first time in history. (The Northeast Passage is the shipping route from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia.) This route can shave numerous days off Asia-Europe voyages versus going through the Suez Canal, so expect to see more of this in the future.

This past summer (Summer 2017), a Russian commercial vessel, a tanker carrying liquid natural gas, transited the Arctic’s Northeast Passage without an icebreaker for the first time in history. (The Northeast Passage is the shipping route from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia.) This route can shave numerous days off Asia-Europe voyages versus going through the Suez Canal, so expect to see more of this in the future.

- And then this winter (Winter 2017-2018), another commercial vessel, another tanker carrying liquid natural gas, transited the Arctic’s Northeast Passage without an icebreaker in the opposite direction in winter. (Check out a pretty amazing time-lapse video of that voyage here.) Shipping firms are now investing in additional ships that can make this transit.

- On the other side of the Arctic, a Finnish icebreaker transited the Northwest Passage in July 2017, the earliest summer transit on record. (The Northwest Passage is the sea route from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific through Canada’s Arctic archipelago that was first navigated by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen between 1903 and 1906.) In total, 33 ships made the full Northwest Passage transit in 2017, up from the previous high of 20 in 2012.

- Of these 33 ships, four were actually tourist vessels. And they weren’t just any old tourist vessels. The 13-story Crystal Serenity, which was the first tourist vessel to make the transit through the Northwest Passage in 2016 and which did it again in 2017, carries over 1,500 guests and crew members. The cost? Over US$20,000 per person.

- This is likely just the vanguard too. Tourism, some of it “last-chance tourism”, is booming in the Arctic. More than a quarter of a million cruise ship passengers passed through Iceland in 2016, up from approximately 8,000 in 1990. The Russian Arctic saw a 20 percent rise in tourists, many from China, in 2017. And some experts believe that cruise lines in the Arctic may start using larger and larger ships.

- In a bit of other shipping news, China just announced its intent to develop a “Polar Silk Road” through the Arctic in areas opened up by sea ice melt. Chinese ships have transited both the Northeast and Northwest passages in the past few years, and China’s increasing interests in oil and gas development, mining, fishing, tourism, and possibly military deployment in the region are making Arctic nations nervous.

- Some very positive environmental and safety-minded maritime news did come out of 2017. On January 1, 2017, the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code went into effect for the Arctic. The Code lays out mandatory guidelines for ships crossing the polar regions, including rules for the design, construction, equipping, and operation of ships working in Arctic and Antarctic ecosystems; training requirements for their crews; and ways they need to protect the environment.

These rules are critical for mariner and passenger safety because ships working in the polar regions face unique risks – including extreme weather conditions, a lack of accurate nautical charts and other navigational aids, and lack of search and rescue capabilities nearby. (A good example of these problems is the cruise ship Clipper Adventurer grounding in 2010. It was following a course based on soundings made in the 1960s using old technology, and it ran aground on an unanticipated shoal. The incident dumped ballast and fuel into Coronation Gulf in the Canadian Arctic archipelago. Twenty-eight (28) passengers and 69 crew members were stranded for two days before the Canadian Coast Guard could pick its way through poorly charted waters to come rescue them.)

These rules are critical for mariner and passenger safety because ships working in the polar regions face unique risks – including extreme weather conditions, a lack of accurate nautical charts and other navigational aids, and lack of search and rescue capabilities nearby. (A good example of these problems is the cruise ship Clipper Adventurer grounding in 2010. It was following a course based on soundings made in the 1960s using old technology, and it ran aground on an unanticipated shoal. The incident dumped ballast and fuel into Coronation Gulf in the Canadian Arctic archipelago. Twenty-eight (28) passengers and 69 crew members were stranded for two days before the Canadian Coast Guard could pick its way through poorly charted waters to come rescue them.)

- Polar Code rules are also critical for ecosystem protection because the remoteness of polar areas makes cleanup of oil or sewage spills extremely difficult and expensive if not physically impossible. Sea ice distribution is constantly changing, and oil spilled anywhere near sea ice will get trapped under the ice and wind up distributed throughout it due to all of its tiny channels and pores.

- Finally, there are some seafarers who are not appreciating the changing conditions, namely those seafarers traveling below the surface. US Navy submarine operators are reporting that current conditions in the Arctic are the most hazardous they’ve ever encountered there because of the increase in ice floes.

Oil drilling may also be ramping up in the Arctic

- Although the offshore areas north of the Arctic Circle have been estimated to have considerable amounts of oil and gas (~10% of the world’s undiscovered oil and gas), most offshore drilling projects in the area have been abandoned due to the hazards and expense of working in Arctic conditions, low oil yields, and low oil prices.

- This may be changing, however, as Russia and Norway begin dramatically increasing their offshore oil and gas extraction in the region. Russia currently has four oil wells up and running in the Pechora Sea and plans to add 28 more. And Norway has just granted 10 production licenses in the Barents Sea. Environmental groups that filed lawsuits in Norway to stop the drilling on the grounds that it would violate the Paris agreement on climate change and the Norwegian constitution were just defeated in court.

- In US waters, the Italian energy company Eni has received a permit to drill exploration wells in the US Beaufort Sea. And large portions of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas that are currently off-limits to oil and gas leasing may become available under a new proposed plan from the Trump administration.

2017 also brought lots of news about pollution in the Arctic

- Obviously, increases in vessel traffic and oil and gas drilling increase the likelihood of pollution, e.g., oil spills, sewage releases, etc., in the Arctic. Of particular concern is the heavy fuel oil (HFO) used by many ships transiting the Arctic. Burning HFO emits more air pollutants – including “black carbon” particles that fall on snow and ice and increase melt rates – than other fuels, and HFO is more difficult to clean up. Environmental organization are calling for a ban of HFO use in the Arctic, similar to the current HFO ban in the Antarctic.

- Of course, there is also plastic – big chunks of polystyrene sitting on remote sea ice in the central Arctic Ocean; discarded fishing gear; microplastics in seabirds from around the region; microplastics in mussels in the Norwegian Arctic; high concentrations of plastic bonded into Svalbard sea ice; and high concentrations of plastic in Greenland and Barents seas waters, probably due to transfer from the North Atlantic.

- Pollution isn’t just coming from oil, fuel, and plastic either. 2018 has already brought us a whole new horror. A new study estimates that there are 50 Olympic swimming pools worth of mercury that are currently trapped in the world’s permafrost (much of it in the Arctic) waiting to be released by thawing. This is twice as much mercury as in the rest of the earth’s atmosphere, soils, and oceans combined. Mercury is a powerful neurotoxin that does tremendous harm to humans and marine life. This finding may help explain the high levels of mercury in Arctic marine life – polar bears, beluga whales, seals, birds, and fish – that scientists have observed for decades.

- And a final, kind of odd pollution source – each launch of a Russian “Rokot” space vehicle may be dumping tons of fuel into Russian and Canadian Arctic waters.

And, finally, recent news about marine protected areas (MPAs) in the Arctic

- As of May 2017, 334 marine protected areas (MPAs) protected 4.6% (~ 860,000 km2) of the Arctic, about half of the Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 goal of 10%. Moreover, most of the existing MPAs are small and not well coordinated.

- Since May, Canada has designated several new MPAs to protect sensitive benthic habitats in the eastern Arctic.

- Finally, IUCN, the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, and the Natural Resources Defense Council recently identified seven Arctic marine areas that could potentially qualify for World Heritage status. Currently, only one Arctic site is recognized by the World Heritage Marine Programme – the Russia Federation’s Natural System of Wrangel Island.

Photo credits:

Record sea ice minimum in the Arctic in 2007. NASA.

Melt streams on the Greenland Ice Sheet on July 19, 2015. NASA.

Arctic. US Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook.

Polar bear seen ice cruising in the Arctic. Gary Bembridge. Licensed under Creative Commons.

Map of the Arctic region showing shipping routes Northeast Passage, Northern Sea Route, and Northwest Passage, and bathymetry. Arctic Council.

Russian cruise ship in Norway. Thomas Hallermann/Marine Photobank.

[1] Different sources use different geographic ranges for what is considered “the Arctic”. In this Skimmer, we use the term loosely to denote the Arctic Ocean and at times the coastal areas and marginal seas around it. If you need more specificity as to what area is encompassed in any individual use of Arctic in this Skimmer, please refer to the accompanying links for more information. Unfortunately, we were not able to cover many other critical aspects of Arctic change, particularly changes to terrestrial ecosystems and impacts on indigenous Arctic peoples.